You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Training Load and Adaptation in Rehabilitation

In sports rehabilitation, optimizing training load is critical for both recovery and performance enhancement. Jason Tee explores training load as exposure and dose, discusses the factors influencing adaptation beyond physical load, and introduces the ATEMPT tool as a means to measure adherence and predict rehabilitation success.

Golden State Warriors forward Jimmy Butler III suffers an apparent injury during the first quarter during game two of the first round for the 2024 NBA Playoffs against the Houston Rockets at Toyota Center. Mandatory Credit: Troy Taormina-Imagn Images

When training load is insufficient, adaptation is unlikely to occur, while an excessive training load may cause fatigue and maladaptation. A well-structured training load ensures that athletes recover effectively while making the necessary adaptations to return to competition. However, training load is a complex concept, and understanding it beyond simply increasing or decreasing workload is essential for sports injury professionals.

One common mistake in rehabilitation settings is assuming that increasing workload over time will lead to a predictable recovery trajectory. However, as many rehabilitation professionals have witnessed, two athletes undergoing the same rehabilitation program can have vastly different outcomes. A footballer recovering from an ACL tear may return to full fitness within six months, while another player with the same injury may struggle to regain pre-injury performance. What accounts for this discrepancy? Understanding training load, stimulus, adherence, and individual variability is key to answering this question.

“…understanding training load requires more than just tracking volume and intensity.”

Exposure and Dose

A group of sports scientists from the University of Technology Sydney have completed some important work defining concepts of training load and aligning them with definitions in other medical fields such as epidemiology(1). They have conceptualized the training load in terms of exposure and dose. Exposure is the overall volume and type of training an athlete undergoes, whereas dose accounts for the internal physiological impact of that training. Importantly, for a training stimulus to be effective, there must be a causal relationship between the exposure and the desired adaptation. Simply exposing an athlete to a training load does not guarantee improvement—adaptation occurs only if the dose elicits the intended physiological response.

Consider a long-distance runner recovering from a stress fracture. If their rehabilitation plan prescribes low-intensity cycling without progressive impact training, they may maintain cardiovascular fitness but fail to stimulate bone remodeling and adaptation needed to return to running. In this case, the dose required to rehabilitate the athlete involves mechanical forces applied through progressively increasing the duration and intensity of weight-bearing running activity. The cycling stimulus would create a mismatch between the intended physiological response and the stimulus required to elicit that response, and highlights why training plans must be carefully tailored to result in the required training effect.

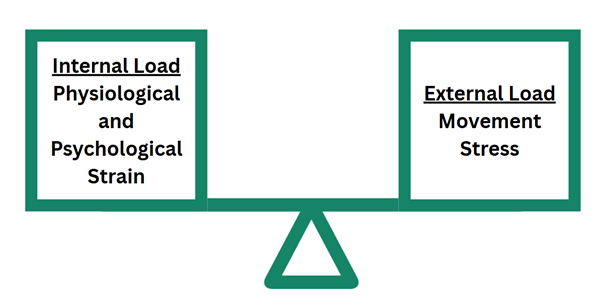

This means that training programs that only prescribe the exercise volume are not specific enough. The choice of exercise stimulus (type of exercise prescribed) must be directly related to the physiological response required for the athlete’s recovery. This is what Impellizzeri and colleagues refer to as a causal relationship – the training plan must be linked to known and predictable physiological response(1). This highlights the importance of planning both external load (the type, volume, and intensity of exercise) and internal load (how an athlete physiologically and psychologically responds to the training)(see figure 1).

A real-world example of training load management is the case of a junior sprinter who suffered a hamstring strain. The initial goal of the rehabilitation program will be to ensure the repair of the lesion within the muscle tissue and the return to full capacity and strength. This would be addressed by exposure to hands-on therapies and strength training. These exposures result in the dose-production of hormonal and local tissue responses that promote the remodelling and repair of the injured muscle. Following the rehabilitation of the muscles’ function and capacity, the challenge of sprinting is neuromuscular coordination. The training exposure must then be adjusted to incorporate eccentric training and sprint mechanics drills so that the dose becomes the rapid recruitment and activation of muscle fibres required for sprinting.

Coaches’ Perceptions of Factors Driving Training Adaptation

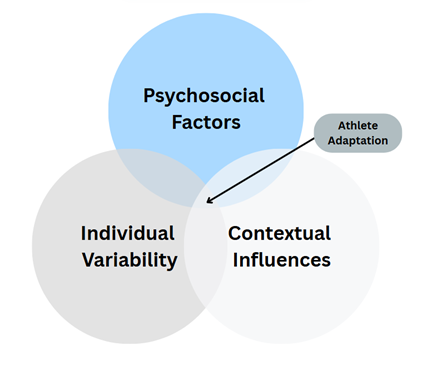

Researchers from Ireland and Germany conducted some groundbreaking research where they surveyed a group of coaches regarding the factors that drive training outcomes(2). The group consisted of over 100 coaches, the majority of whom had post-graduate qualifications and were working with either national or international level athletes. The survey outcomes demonstrated that while coaches consider training exposure and dose important, a range of non-physical factors can influence how well an athlete adapts to training (see figure 2). These include:

- Psychosocial factors: The presence of a supportive community, positive coach-athlete relationships, and psychological resilience can all enhance adaptation.

- Individual variability: Athletes respond differently to the same training load based on genetic, nutritional, and lifestyle factors.

- Contextual influences: Sleep quality, stress levels, and personal motivation all play roles in whether an athlete successfully adapts to training loads.

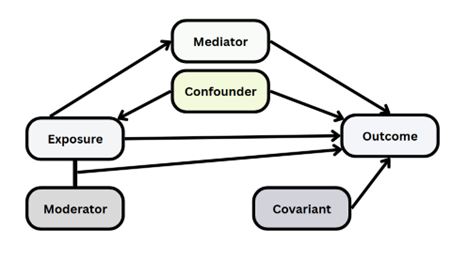

This demonstrates that in the experience of elite coaches, training adaptation is not purely a linear function of workload. This realization is predicted by the Australian research group’s work on training load as exposure and dose(1). It is well noted in fields such as virology and epidemiology that even when there is a direct causal relationship between the exposure and the outcome, mediators and confounding variables affect this relationship. A simple example of this is the case of a runner that is attempting to improve their 10km running time. Even with a perfectly designed training programme that prescribes the exact correct stimulus in terms of training intensity and volume, the effect of this stimulus could be blunted if the athletes’ nutritional or sleep habits are poor. The exposure would be correct, but the physiological response would be affected by other factors that the coach may be unable to account for.

“When training load is insufficient, adaptation is unlikely to occur…”

The effectiveness of training exposures is not always mediated only by physiological means, and psychosocial factors often play a role. Take, for instance, a rugby player recovering from a shoulder injury. If they are well-integrated into their team environment—engaging in tactical discussions, supporting teammates, and feeling valued—they will likely remain motivated and engaged with their rehabilitation program. Conversely, an athlete who feels isolated due to injury may struggle with adherence and experience slower progress. This means that sports injury professionals should consider a holistic approach to rehabilitation, incorporating strategies that go beyond simple load progression.

Communication with coaches, understanding athlete well-being, and fostering an environment that supports psychological recovery can be just as crucial as prescribing the right exercises.

Measuring Exercise Adherence

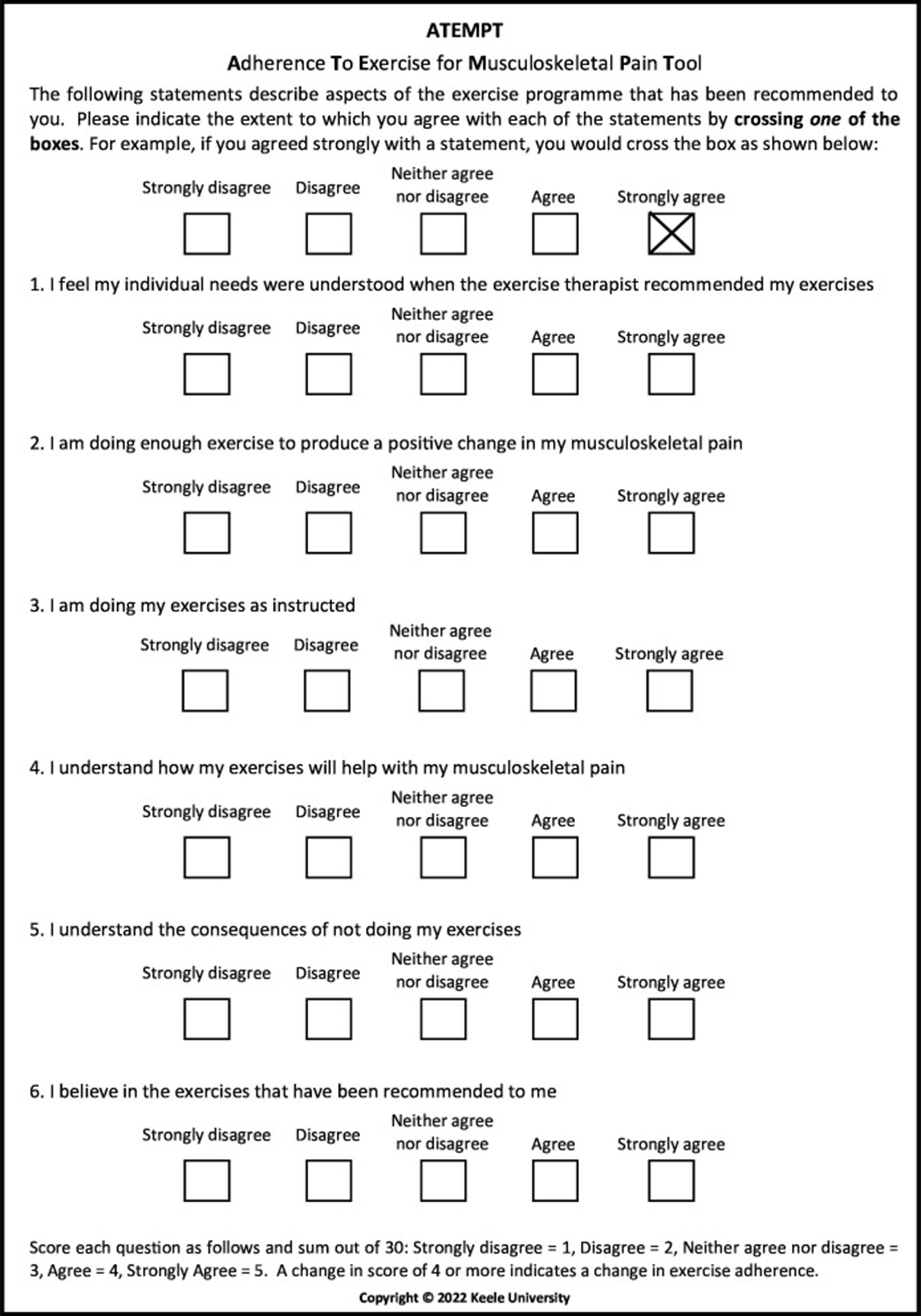

One of the foremost challenges for any rehabilitation professional is adherence to the prescribed training plan. There is often a discrepancy between prescription and what the injured athlete actually does. Researchers from Keele University in the UK aimed to address this problem by designing the Adherence to Exercise for Musculoskeletal Pain Tool (ATEMPT)(3).

The tool provides a structured way to measure an athlete’s rehabilitation adherence. In the context of training load theory, adherence can be viewed as a measure of actual training dose, since an athlete who does not complete their exercises as prescribed is not receiving the intended training stimulus. Furthermore, adherence is likely influenced by many of the same factors that coaches recognize as affecting adaptation—motivation, social support, and athlete-coach relationships. By tracking adherence through the 6-item Adherence To Exercise for Musculoskeletal Pain Tool (ATEMPT) tool, practitioners can identify potential barriers to rehabilitation success and adjust interventions accordingly. This could involve modifying the training program to improve engagement, addressing psychological challenges, or increasing support structures around the athlete (see figure 4).

A key takeaway is that non-adherence does not necessarily reflect laziness or lack of commitment. It may instead indicate a poorly designed rehabilitation program that does not align with the athlete’s psychological and physical needs. Practitioners working with an injured marathon runner, for instance, may find that the athlete struggles with gym-based exercises due to a preference for endurance-based movement. Adjusting the program could ensure that the exercise exposure comes closer to the dose that the rehabilitation professional is hoping to deliver through the training program.

“Simply exposing an athlete to a training load does not guarantee improvement…”

Clinical Recommendations

For rehabilitation practitioners, understanding training load requires more than just tracking volume and intensity. It involves ensuring that training exposure leads to a meaningful physiological dose, recognizing that various factors influence training adaptation, and using tools like the ATEMPT to assess adherence.

By integrating these insights into practice, professionals can optimize rehabilitation protocols, improve athlete outcomes, and enhance the likelihood of a successful return to sport. Ultimately, training load management in rehabilitation is both an art and a science. It requires not only careful data tracking but also a deep understanding of the athlete’s individual context, motivations, and the broader social environment in which they are recovering.

As a final thought, sports injury professionals should ask themselves: Am I simply prescribing exercises, or am I designing a rehabilitation experience that maximizes adherence and adaptation? The answer to that question could be the difference between an athlete making a full recovery or struggling with recurrent injuries.

References

1. Sports Med. 2023 Sep;53(9):1667-1679.

2. Sports Med. 2023 Dec;53(12):2505-2512. 2023 Aug 8.

3. Br J Sports Med. 2024 Jan 3;58(2):73-80.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.