You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

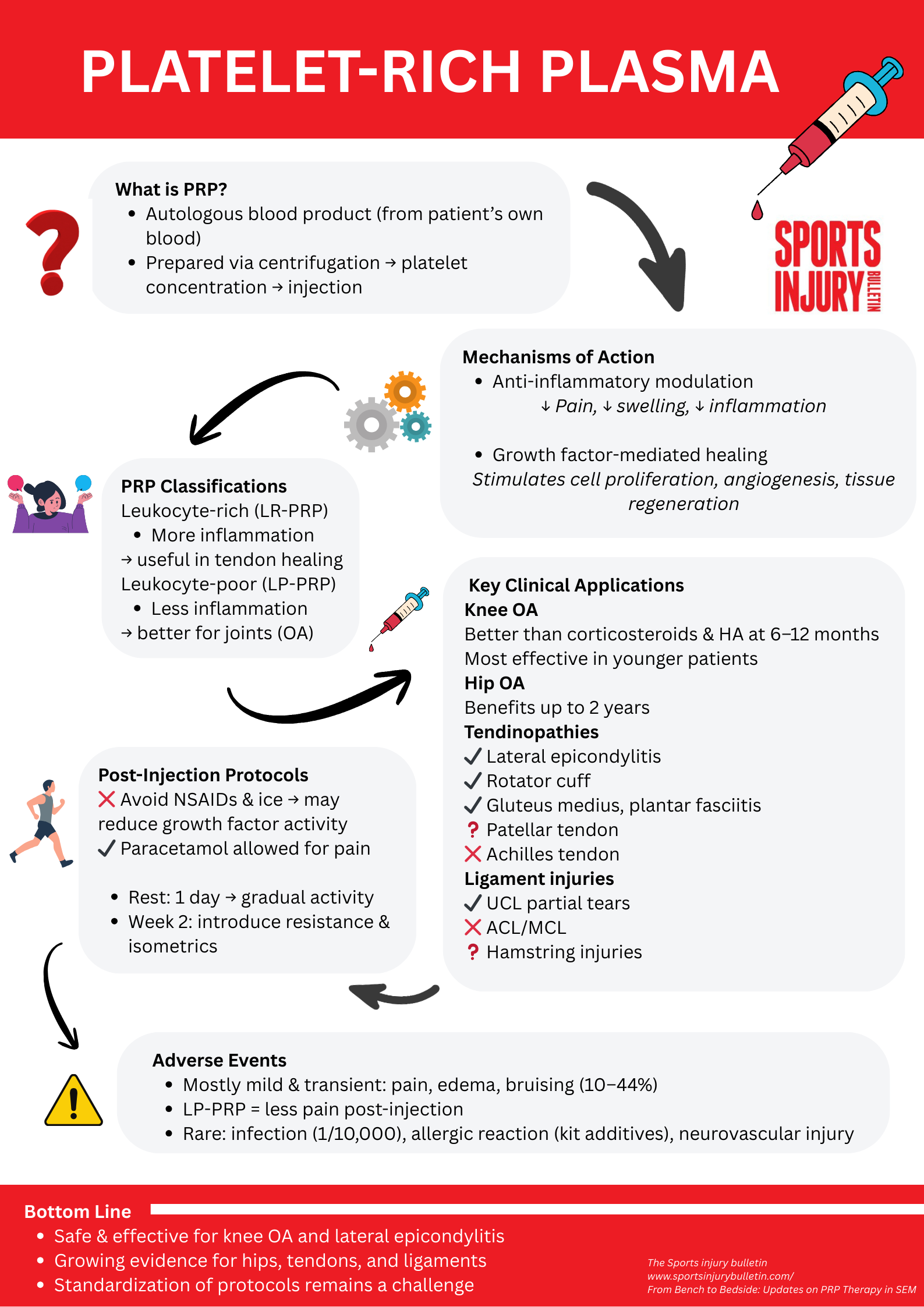

From Bench to Bedside: Updates on PRP Therapy in SEM

Platelet-rich plasma therapy is emerging as one of the most promising regenerative tools in sports and exercise medicine. Collin Filley uncovers the latest evidence and discusses protocols and applications to aid clinical decision-making.

San Diego FC defender Aiden Harangi (23) is helped off of the pitch after suffering an injury during the first half against the San Jose Earthquakes at PayPal Park. Mandatory Credit: Darren Yamashita-Imagn Images

Mechanism

The field of regenerative and sports medicine is continuously advancing, with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) representing a significant area of progress. Initially, clinicians utilized PRP in the field of hematology for conditions such as thrombocytopenia, and they have expanded its use in surgery, cosmetics, and musculoskeletal medicine(1). The treatment is based on the therapeutic application of the body’s intrinsic healing mechanisms. A growing body of scientific literature provides insights into PRP’s mechanisms of action, optimal preparation protocols, and expanding clinical indications, positioning it as a relevant intervention for orthopedic injuries.

Platelet-rich plasma is an autologous blood product derived from a patient’s whole blood. Its preparation involves venipuncture followed by centrifugation, a process that separates blood components by density to concentrate platelets. Clinicians collect the isolated platelet-rich layer for injection into the target anatomical site. Then, they inject the formulation into the target site, with more elusive locations commonly being located under ultrasound or fluoroscopic guidance.

“Evidence for PRP in ligamentous injuries is less extensive but emerging”

Clinicians hypothesize the effects of PRP to arise from two primary mechanisms, driven by the release of growth factors and signaling molecules from activated platelets(2):

- Anti-inflammatory modulation: Following injection, PRP induces a localized anti-inflammatory response. This response is mediated by the release of various cytokines and soluble factors, including interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (sTNF-R) I and II, IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and interferon-γ(2). These molecules contribute to the downregulation of pro-inflammatory pathways, reducing inflammation, edema, and pain(2).

- Growth factor-mediated tissue regeneration: PRP functions as a concentrated source of growth factors, often at supraphysiological levels. Key growth factors include transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)(3). These factors stimulate cellular proliferation and differentiation, enhance extracellular matrix synthesis, promote angiogenesis, and accelerate tissue repair(3). This molecular cocktail suppresses inflammation, mitigates pain, and reduces ongoing tissue damage. Additionally, the presence of fibrinogen and other clotting factors in PRP facilitates the formation of a fibrin matrix, which acts as a scaffold for cellular attachment and organized tissue healing, particularly relevant for cartilaginous and soft tissue injuries(4).

A significant challenge in the research and clinical application of PRP is the lack of standardization across preparation methods, dosing, and nomenclature. This variability complicates direct comparative analyses between studies. To address this, medical societies in orthopedics and sports medicine have initiated efforts to standardize PRP protocols.

A recent consensus statement proposed classifying PRP based on platelet count, leukocyte count, and red blood cell count(5). This classification aims to enhance clarity in describing diverse PRP preparations. Platelet concentration is a critical attribute, and one that supervising agencies target for standardization due to its ability to be objectively measured. Most commercial kit preparations typically contain two-and-a-half to eight times the platelet concentration of whole blood(6). Higher platelet concentrations correlate with improved clinical outcomes. For example, Italian researchers recommend a cumulative target of 10-12 billion platelets across multiple injection sessions for optimal therapeutic efficacy(7).

The inclusion or exclusion of leukocytes defines leukocyte-rich (LR-PRP) and leukocyte-poor (LP-PRP) formulations. Intra-articular pathologies such as osteoarthritis tend to show better results with leukocyte-poor formulations. Clinicians attribute this preference to the reduced neutrophil content in LP-PRP, as neutrophils are highly inflammatory and can potentially impede tissue healing and increase post-injection pain(8). Conversely, a higher monocyte content in some PRP preparations has anabolic effects and improves tissue repair, leading to the development of monocyte isolate-enriched formulations for specific regenerative applications(9). While clinicians still debate the optimal leukocyte content, LR-PRP formulations, despite potentially causing more immediate post-injection pain due to neutrophil-mediated inflammation, might offer benefits in tendon healing due to a broader range of growth factors and immune cell activation(10).

Knee Osteoarthritis

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) represents the pathology with the most extensive literature supporting PRP interventions. Platelet-rich plasma is more effective than hyaluronic acid (HA) and corticosteroid injections in improving joint function and reducing WOMAC (Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index) pain scores over 6-12 months(8). While corticosteroids provide short-term pain relief (four to six weeks), PRP demonstrates superior and more durable efficacy at more extended follow-up periods. It has greater efficacy in younger patients with less advanced radiographic disease (Kellgren-Lawrence grades one to three)(11). Improvements in WOMAC scores are typically observed after two months and can persist for up to one year(9).

Hip Osteoarthritis

Application in hip osteoarthritis is less robust than support for KOA, but there is promise. Intra-articular PRP injections can lead to statistically significant improvements in pain scores and functional outcomes (e.g., Hip Disability and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score) when compared to HA and corticosteroid injections. Patients show continuous improvement from two to three months post-injection and remain at better scores at six and 12 months, and even up to two years(12).

Lateral Epicondylitis

Tendinopathy is the second most common pathology with evidence supporting PRP therapy. Lateral epicondylitis is the most frequently studied tendinopathy, showing consistent positive outcomes. Similar to its effects on KOA, PRP demonstrates a slower onset of pain relief but provides superior and more durable long-term outcomes when compared to the injection of corticosteroid into the affected tendon(13). Patients experience relief from pain and improvement in function consistently up to two years(14). This response is consistent with the theory that tendinopathies are degenerative pathologies as opposed to purely inflammatory conditions.

Rotator Cuff Tendinopathy

Rotator cuff tendinopathy data indicate that PRP injections provide significant short- to medium-term pain relief (e.g., up to six or 12 months) and improved shoulder function when compared to placebo or corticosteroid injections(15). Data beyond this period is much less consistent and does not demonstrate sustained superiority over control groups (e.g., placebo, corticosteroids, or physical therapy alone)(16). Evidence also supports PRP use in gluteus medius tendinopathy and plantar fasciitis(17,18). While the effectiveness in patellar tendinopathy is unclear(19). Conversely, PRP therapy has poor results in Achilles tendinopathy(20).

“Consensus on optimal post-injection protocols for PRP is still evolving.”

Ligamentous and Other Soft Tissue Injuries

Evidence for PRP in ligamentous injuries is less extensive but emerging. It may have applicability in ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injuries in throwing athletes, with the highest effectiveness in low-grade (grade one and two) partial UCL tears. For high-grade partial tears or complete (grade three or four) tears, the efficacy of PRP significantly diminishes(21). For example, American researchers from the OrthoCarolina Research Institute demonstrated that a single ultrasound-guided PRP injection resulted in 75% of patients with partial tears returning to play at an average of 82.1 days(22).

Evidence for standalone PRP treatment in major knee ligamentous injuries (e.g., anterior cruciate ligament tears, medial collateral ligament tears) is minimal. While short-to-medium term improvements in pain and some functional scores may be observed, PRP generally does not lead to a clinically meaningful long-term improvement in knee stability(23). Additionally, there is no significant difference in functional outcomes at three, six, or 12 months when comparing PRP-augmented surgical repair to non-augmented repair(24). Furthermore, athletes with hamstring tendon injuries may benefit from PRP, although the evidence is minimal(25).

Post-Injection Protocols

Consensus on optimal post-injection protocols for PRP is still evolving. Standard recommendations advise patients to avoid anti-inflammatory medications (e.g., NSAIDs) and ice for approximately two weeks pre-injection and at least one month post-injection. Clinicians recommend these practices based on concerns that these interventions may downregulate growth factor and cytokine activity, potentially reducing PRP efficacy(26). Paracetamol/acetaminophen is not anti-inflammatory and generally regarded as appropriate for the treatment of pain after injection.

Protocols typically recommend activity restriction for one day post-injection, followed by a gradual return to activity as tolerated over the subsequent weeks. At two weeks, most protocols recommend a gradual and progressive introduction of resistance exercises and functional loading(27). Isometrics are the classic first-line exercise for building strength without stressing joints.

Adverse Events

Platelet-rich plasma injections demonstrate a favorable safety profile. Common adverse events are mild and transient, including localized pain, mild edema, and bruising at the injection site. Between 10-44% of patients report transient pain in the immediate hours post-injection(28). Leukocyte-poor formulations are associated with decreased immediate post-injection pain and edema. In contrast, leukocyte-rich formulations may increase immediate pain scores due to pro-inflammatory effects from higher neutrophil content(7,9).

The autologous nature of PRP decreases the risk of allergic reactions. However, in rare case reports, researchers attribute allergic reactions to additives from commercial kits(29). Infection rates are low, comparable to other sterile pharmaceutical injections (estimated at 1 in 10,000 injections)(30). Infrequent reports of neurovascular bundle damage exist, but as with any other injectable intervention, clinicians must take steps such as using imaging guidance to minimize risk.

Platelet-rich plasma is an increasingly effective and safe biological intervention in musculoskeletal medicine. The highest degree of effectiveness continues to be in knee osteoarthritis and select tendinopathies such as lateral epicondylitis. Ongoing research aims to standardize protocols, optimize application, and further delineate its long-term disease-modifying potential, solidifying its role in patient-centered orthopedic injury management.

“Platelet-rich plasma is an increasingly effective and safe biological intervention in musculoskeletal medicine.”

References

1. PM R. 2020;12(4):373-378.

2. Cureus. 2024;16(7):e65636. Published 2024 Jul 29.

3. J Mater Chem B. 2025;13(30):9001-9022. Published 2025 Jul 30.

4. Arthritis Res Ther 16, 204 (2014).

5. Arthroscopy. 2024;40(2):470-477.e1.

6. Am J Sports Med. 2008 Jun;36(6):1171-8.

7. J Clin Med. 2025;14(8):2714.

8. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016;44:792–800.

9. J. Clin. Med. 2024;13:4816.

10. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(11):2213-2221.

11. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(9):2487-2497.

12. Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7(3).

13. Am J Sports Med. 2024;52(10):2646-2656.

14. Bioengineering (Basel). 2025;12(6):617. Published 2025 Jun 5.

15. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(5):1584-1591.

16. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(5):1130–1137.

17. J Burns Trauma. 2021;11(1):1-8. Published 2021 Feb 15.

18. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47(7):1654–1661.

19. JAMA. 2021;326(2):137–144.

20. Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(14):3858-3869.

21. Arthroscopy. Published online July 3, 2025.

22. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2024;32(5):1143-1159.

23. J Sport Rehabil. Published online July 4, 2025.

24. PM R. 2024;16(9):1023-1029.

25. UW Sports Medicine Rehabilitation Guidelines for Tendons Status-Post Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Injection. 2017. Accessed July 9, 2025.

26. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24(1):926. Published 2023 Nov 30.

27. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(10):e14702.

28. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2024;222(3):e2330458.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.