Rupture to Run: Post-Achilles Tendon Repair

Achilles tendon ruptures often necessitate surgical intervention followed by a structured rehabilitation program. Comprehending the anatomy, surgical techniques, prevalence, and management strategies is essential. Nicole McGregor discusses the current research and expert opinions to illuminate effective rehabilitation protocols.

Golden State Warriors forward Gui Santos and guard Gary Payton II vie for a loose ball with Utah Jazz center Kyle Filipowski during the first quarter at Chase Center. Mandatory Credit: D. Ross Cameron-Imagn Images

The Achilles tendon (AT) is the largest, strongest, and most powerful spring in the human body, primarily functioning to provide a tendinous connection for the soleus and gastrocnemius muscles to the calcaneus. It endures tremendous loads, particularly during eccentric calf contractions, with forces reaching up to 15 times body weight during activities like gymnastics landings(1). Rupture of the AT is a traumatic injury requiring significant force and often results in lasting functional deficits, regardless of the treatment approach(1). In recent years, there has been an increase in AT ruptures, particularly in explosive sports such as basketball, football, and gymnastics, with a notable prevalence among athletes aged 20-39, particularly males(2).

“In recent years, there has been an increase in AT ruptures…”

Clinicians categorize treatment for acute AT rupture into surgical and non-surgical management. Furthermore, they generally prefer surgical repair for elite athletes due to superior outcomes in reducing re-rupture rates and restoring plantar flexor strength. Open repair remains the gold standard due to its strength and early mobilization benefits(3). Minimally invasive options, like the SpeedBridge™ technique, aim to combine the benefits of open and percutaneous repairs, though concerns about calcaneus pain from suture anchors persist(1). Although less common in elite sports, non-operative management offers comparable outcomes when practitioners initiate early functional rehabilitation(2).

Rehabilitation Stages

Surgical site protection phase (0-2 weeks): Rehabilitation post-Achilles tendon repair involves several phases tailored to specific recovery goals. In the immediate post-operative phase (0-2 weeks), the primary focus is managing pain, controlling swelling, and protecting the surgical site (see table 1). This period involves immobilization, often in a CAM boot with heel wedges, to promote wound healing and minimize stress on the repair(1). Clinicians can initiate proximal and core strengthening exercises during this phase, emphasizing maintaining proximal muscle strength while avoiding excessive sweating near the wound to reduce infection risk(1).

“Several factors influence rehabilitation success and RTS timelines.”

Table 1: Achilles tendon repair management(1)

| Stage | Goals | Interventions | Key Milestones | Precautions |

| Post-op (0-2 weeks) | 1. Protect surgical site, 2. Maintain proximal muscle strength, 3. Minimize pain and swelling. |

Immobilization in a short cast or CAM boot, proximal strengthening, ankle AROM (dorsiflexion ≤ 0°). | Wound healing, cast removal, and surgical clearance. | Post-op complications, no passive dorsiflexion, no active dorsiflexion > 0°. |

| Early Rehab (2-6 weeks) | 1. Reduce pain, 2. Initiate isometric plantarflexion, 3. Reach ankle ROM within phase limits, 4. Maintain LL, core, and cardiovascular fitness. |

Progressive ambulation (start with PWB with CAM boot with heel lifts), AROM dorsiflexion to 0° with knee in 90° flexion, sub-maximal isometrics, proximal strengthening with/without BFR. | Weight bearing as tolerated in CAM boot, ankle dorsiflexion AROM to neutral, reduced pain and swelling. | No passive dorsiflexion with knee flexed past neutral for 4 weeks, no passive dorsiflexion with the knee extended for 10 weeks, monitor resting dorsiflexion tension in prone position with knee flexed. |

| Intermediate Rehab (6-12 weeks) | 1. Increase ankle dorsiflexion ROM without excessive elongation stress, 2. Normalize gait pattern, increase ankle plantarflexion strength. |

Double-leg to single-leg heel raise progression, heel raises on heel wedge to end range of motion, continued BFR use. | Double-leg calf raise through full ROM. | Monitor resting dorsiflexion tension in prone position with knee flexed. |

| Late Rehab (12-24 weeks) | 1. Increase single-leg plantarflexion strength and endurance throughout full ROM. | Double-leg progression, pogo jumping with band resistance. | Completion of plyometric progression, successful completion of return to run program. | Monitor loading. |

| Return to Sports (24+ weeks) | 1.Isokinetic/isometric strength >90% limb symmetry index (LSI). | Progress plyometric, local and global strength, and sport-specific training. |

Strength >80% contralateral side, strength ≥2.5-3.0x body weight with seated calf isometric, double-leg CMJ asymmetries <20%, single-leg jump asymmetries <20%. | Monitor workload. |

Controlled mobilization phase (2-6 weeks): The primary goal during this phase is to accommodate ambulating in the boot and provide controlled tension to the repair while avoiding tendon elongation. Accelerated weight bearing protocols typically progress from partial to full weight bearing by 4-6 weeks. Clinicians must educate patients about load progression and manage walking volumes to prevent tendon overload(1). Furthermore, they can assess passive tension with the patient positioned in prone, knee bent to 90°, and hip in a neutral position to ensure the tendon is not overstressed(1). Following progress to FWB in the CAM boot, the surgeon must provide clearance to initiate gait training in an athletic shoe with heel lifts, which fosters the gradual return to normal walking.

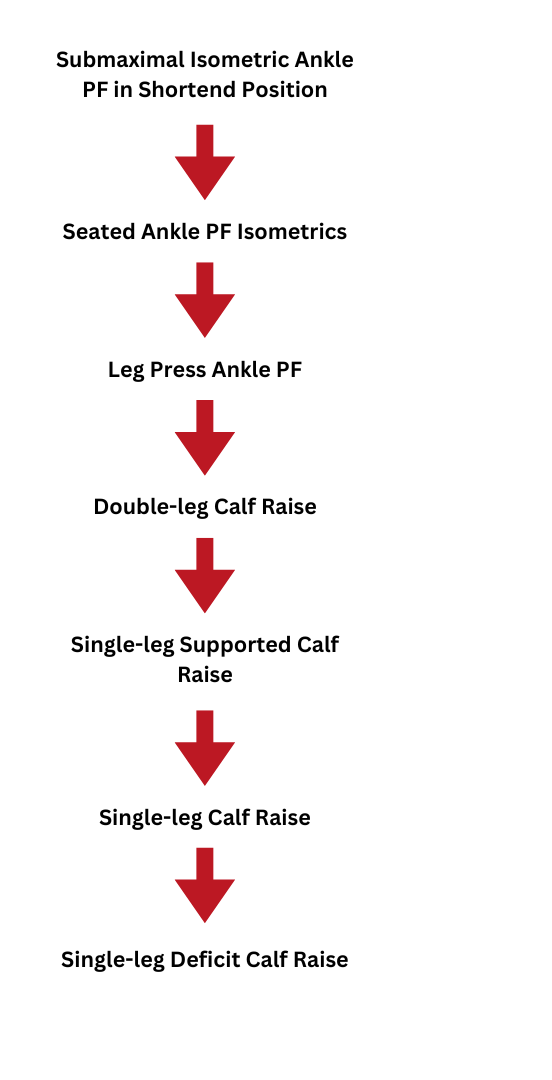

The intermediate rehabilitation phase (6-12 weeks): This phase focuses on improving ankle dorsiflexion ROM without excessive elongation stress and normalizing gait mechanics. Exercises progress from double-leg to single-leg heel raises, with continued use of blood flow restriction therapy (BFRT) to preserve muscle strength (see figure 1). A key milestone during this phase is achieving a double-leg calf raise through full ROM(1). Clinicians must monitor resting dorsiflexion tension to avoid excessive elongation(1).

Late rehabilitation phase (12-24 weeks): This phase emphasizes gradual and progressive loading, with strength measures greater than 70-80% LSI, and initiation of plyometric progression/return to running. Restoring sport-specific ROM, fundamental local and global strength, and neuromuscular control is critical. Clinicians can introduce exercises such as eccentric calf raises, single-leg squats and plyometric drills like box jumps and shuttle runs to enhance strength and power(1). Key milestones include returning to plyometric activities such as running and jumping, which rely on the stretch-shortening capabilities of the AT complex. Low amplitude impact activities like ladder drills and band-assisted pogo hops introduce slow stretch-shortening cycle activities. Timelines to initiate running are highly variable but typically begin after 12-16 weeks post-surgery(1).

Return to Sport

Effective RTS testing is essential for assessing an athlete’s readiness. Key performance indicators include strength, muscular endurance, power, and reactive strength. Clinicians can evaluate strength using isokinetic testing, aiming for a limb symmetry index (LSI) greater than 90%(1). Muscular endurance tests, such as the single-leg heel rise, should also meet a 90% LSI benchmark(1).

Power assessments, including countermovement and single-leg hops, provide insights into SSC ability, with interlimb asymmetries ideally below 10-20%(1). Clinicians can measure reactive strength using drop vertical jumps and should target an RSI of over 1.5 for double-leg and 0.5 for single-leg(1).

Key Insights on Achilles Tendon Rehabilitation

- Participant Motivation: Personal drive and goal-setting are critical for successful recovery and rehabilitation adherence.

- Social Support: Family and friends provide essential encouragement and practical help, facilitating rehabilitation.

- Healthcare Systems: Confidence in healthcare teams and resource access influence recovery outcomes.

- Rehabilitation Strategies: Controlled mobilization and progressive strengthening are vital phases in recovery.

- Return to Sport: A continuum approach with routine performance testing ensures safe reintegration into athletic activities.

- Psychological and Physiological Factors: Mental readiness and physical fitness significantly impact rehabilitation success and return to sports timelines.

Several factors influence rehabilitation success and RTS timelines. Tendon elongation during recovery can impact outcomes, emphasizing the need for controlled loading(1). Blood flow restriction therapy preserves muscle strength and minimizes atrophy during early rehabilitation. Individual variability in tendon healing and neuromuscular control necessitates personalized rehabilitation plans(3).

Psychological factors also play a crucial role in the recovery process. Athletes’ confidence in their healthcare team and personal motivation significantly impact their rehabilitation journey. Psychological readiness and support systems are critical to successful RTS(4). Return to full sports intensity drives an athlete’s commitment to rehabilitation, underscoring the role of mental resilience(4).

Social and environmental factors further influence recovery. Economic considerations, such as reduced income during sick leave, can affect athletes’ ability to engage in rehabilitation fully(5). Accessibility to facilities and transportation impacts the ease of attending rehabilitation sessions, which can be challenging when mobility is limited(5). Support from family and friends is vital, providing practical help and emotional encouragement throughout the recovery process(5).

“Advancements in surgical techniques and rehabilitation protocols significantly improve outcomes…”

Return to sports rates vary across different sports and rehabilitation protocols. For example, NBA players exhibit deficits in performance metrics such as minutes per game and player efficiency rating in the first two years post-injury(6). Furthermore, elite athletes treated with the Uchiyama method achieved a 100% RTS rate, with an average return time of 22.3 weeks, underscoring the potential of tailored surgical techniques and rehabilitation protocols(7). The Uchiyama method’s protocol, which includes early mobilization and structured progression, supports the importance of customized rehabilitation approaches(7).

Conclusion

Advancements in surgical techniques and rehabilitation protocols significantly improve outcomes for athletes recovering from Achilles tendon ruptures. By adhering to evidence-based practices and tailoring rehabilitation to individual needs, practitioners can facilitate optimal recovery and a successful RTS. Continued research and refinement of rehabilitation strategies will be key to further enhancing recovery trajectories.

References

1. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2024;19(9)

2. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56:515-520

3. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2023;62(5):779-784

4. Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;11(2)

5. The Orthop J Sports Med. 2023;8:4-10

6. Br J Sports Med. 2022;56:515-520

7. JOS Case Reports. 2024;3:25-28

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.