Ulnar collateral ligament damage: an injury of the young

Injuries affecting the medial elbow are common in overhead throwing sports such as baseball pitchers, and javelin throwers(1). The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) is the primary stabilizer of the medial elbow joint and if injury presents, it can become a career-threatening injury in a throwing sport. Treatment can be conservative but in some situations, reconstructive surgery is indicated.

Background

Patients who present with an injury to the UCL are typically adolescents or young adults - most likely due to the activities they participate in during this age range and the predisposing forces to this structure that are encountered. Researchers from the University of Florida, USA studied the age and injury severity in 136 young athletes ranging in ages from 11-22 years(1). Of these patients,101 were baseball pitchers, 12 played softball, eight American football, five javelin throwers, and the rest played ultimate Frisbee, volleyball, gymnastics and mixed martial arts. The mean age at the point of injury was 16.7 years. The authors found that the younger the patient, the more likely they were to be treated conservatively based on a lower degree of injury (based on the data as illustrated in table 1).| Type of injury | Number | Mean age (years) |

|---|---|---|

| Sprain | 60 | 15.9 |

| Partial tear | 39 | 16.9 |

| Complete tear | 36 | 17.6 |

| Re-rupture | 1 | 19.0 |

Age in years, indicating lower-level injuries in younger athletes, with more severe injuries in older age groups. Data extracted from Zaremski and colleagues(1).

The frequency of UCL injuries is becoming more and more pronounced within clinical practice. Over a 16-year period from 2000-2016136 patients were presented. Of these, five injuries were presented between 2000-2003, nine from 2004-2007, 50 from 2008-2012 and 72 from 2013-2016(1). The authors did suggest that the increased frequency of injury could be related to clinicians having increased awareness of injuries relating to the UCL, and lesser sprains being more accurately diagnosed as a UCL strain. However, it is also possible that due to strength and conditioning techniques, athletes are now throwing further, resulting in increased valgus forces.

Since lower grade strains tend to be experienced at a much younger age, it is conceivable to suggest that as athletes grow older, they may experience more severe strains to the UCL. Zaremski and colleagues stated that older more mature athletes can generate more force during the acceleration phase, with up to 50Nm being reported.

They have created a debate as to whether it is the increased force that is applied by the older athletes, or whether it’s the increased volume of throwing taking place at this age resulting in increased of total loading. It is plausible to state that both factors may well be responsible for the increased severity of UCL injury. In addition, if a patient has been a long-term baseball player who suffered an undiagnosed lower grade injury earlier in their life, this may result in a more severe injury later in adult life.

Anatomy and biomechanics

The UCL is a static stabilizer of the medial elbow joint alongside the joint capsule, whereas the elbow has dynamic stabilizers such as the flexor pronator muscle group (see figure 1)(2). These structures all assist in preventing valgus instability at the elbow. Cadaveric studies have shown that the UCL can increase in size through loading, with a mean thickness of 6.2mm in the throwing arm compared with 4.8mm in the non-throwing arm(2).The anterior bundle is the most commonly injured structure with the anterior fibres being the primary restricting factor against valgus forces between 30-90 degrees of elbow flexion(2). By contrast, the posterior band of the anterior bundle stabilizes the fan-shaped structure against valgus forces from 90-120 degrees of elbow flexion. The length of the anterior bundle of the UCL ranges from 4.7cm to 5.4cm(2)The transverse ligament provides no resistance to valgus forces as it doesn’t cross the elbow joint. The anterior and posterior fibers originate at the medial epicondyle of the humerus and attach at the semilunar notch of the ulna(2).

Figure 1: Ulnar collateral ligament of the right elbow

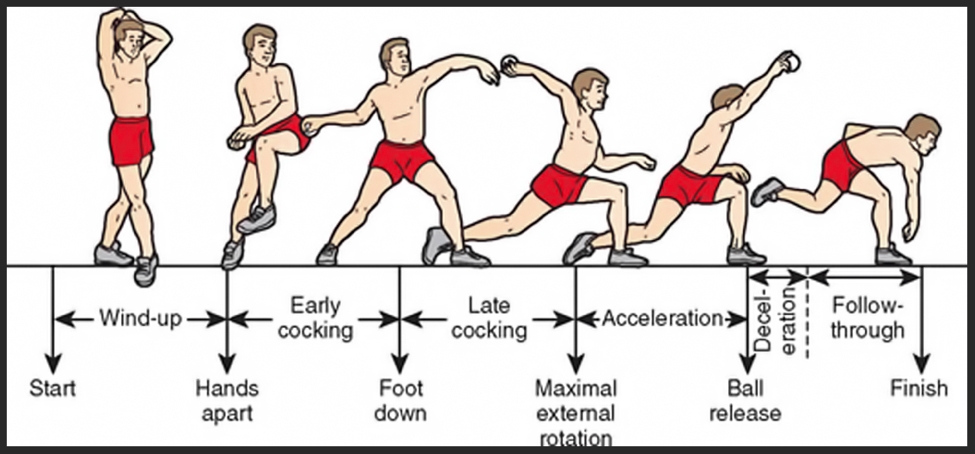

During overhead throwing actions, the UCL is under most strain - receiving 50% of the valgus force(2). An eccentric contraction of the flexor pronator complex helps to absorb the remaining forces. During a baseball pitch, the integrity of the UCL is most compromised at the end of the cocking phase when the acceleration is applied to propel the hand forwards to release the object (see figure 2). At the end of the cocking phase the elbow is often in 90-100 degrees of elbow flexion and therefore the posterior band of the anterior bundle is under the greatest load. Erikson (2)and colleagues stated that the failure load of the UCL is almost replicated in every throw indicating that injury can result if techniques are incorrect. It is essential that a clinician appreciates the forces that the elbow is under in various sports. It is also worth monitoring training loads as this may also be factor as to why injury is presenting.

Figure 2: An illustration of the forces on the medial elbow joint in a baseball pitcher

Examination and assessment

It is important to find out the time at which the pain started and whether it occured during the acceleration phase (which is in 85% of cases) or in the follow through phase (as in 25% of cases)(2). The patient may complain of ulnar nerve symptoms since the ulnar nerve passes in close proximity to the UCL. A patient with a UCL injury may have a flexion contracture, and pain on terminal extension. There are some special tests which test the integrity of the UCL and are depicted in figure 3(2).Figure 3: Valgus stress test in standing and lying

The valgus stress test can be done in either standing or lying – see figure 3 a) and b) - with the elbow flexed to 20-30 degrees of elbow flexion. This tests the anterior band of the anterior bundle. The flexion of the elbow (as similar to that of the knee joint) reduces the osseous constraint of the joint itself. At the point of applied pressure, the therapist palpates along the course of the UCL. Pain or laxity indicates damage to the ligament.

The ‘milking manoeuvre’ test loads the posterior band of the anterior bundle (see figure 4). The arm is positioned into shoulder extension, with external rotation, forearm supination and the elbow flexed to 90 degrees of elbow flexion. The therapist stands behind the patient and pulls their thumb whilst stabilising the shoulder with the other hand. This creates a valgus stress at the elbow and loading to the UCL, with pain and apprehension indicating injury.

Figure 4: ‘Milking manoeuvre’

Execute the moving valgus stress test with the shoulder abducted to 75 degrees (see figure 5). The subject's elbow is maximally flexed, and the shoulder externally rotated whilst a valgus force is applied. Maintain the values stress while quickly extending the elbow to 30 degrees of flexion.

A positive test produces the pain felt during the throwing action between 70-120 degrees of elbow flexion. This test replicates the late cocking and acceleration phase as experienced during a throwing action, and is reported to have a sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 75%. The sensitivity of a test can be explained asthe proportion of people who test positive for a condition among those who actually have the condition. In contrast specificity can be defined as the amount to which a diagnostic test is specific for a particular condition.

Figure 5: Moving valgus stress test

Classification of injury

| Grade I | Oedema in the ligament and is classed as a low level partial tear. |

| Grade II | High grade partial tear of the UCL but with no leakage of fluid into the surrounding tissues - as determined by a magnetic resonance arthrogram (MRA). |

| Grade III | Full thickness tear, with leakage of fluid into the surrounding tissues as determined on MRA. |

| Grade IV | Two lesions at different points on the UCL. |

Joyner and colleagues have described a four-point grading system to classify injury status(3). It is important that pain is reported in accordance with the lesion site for a diagnosis of UCL to be confirmed.

Treatment and rehab

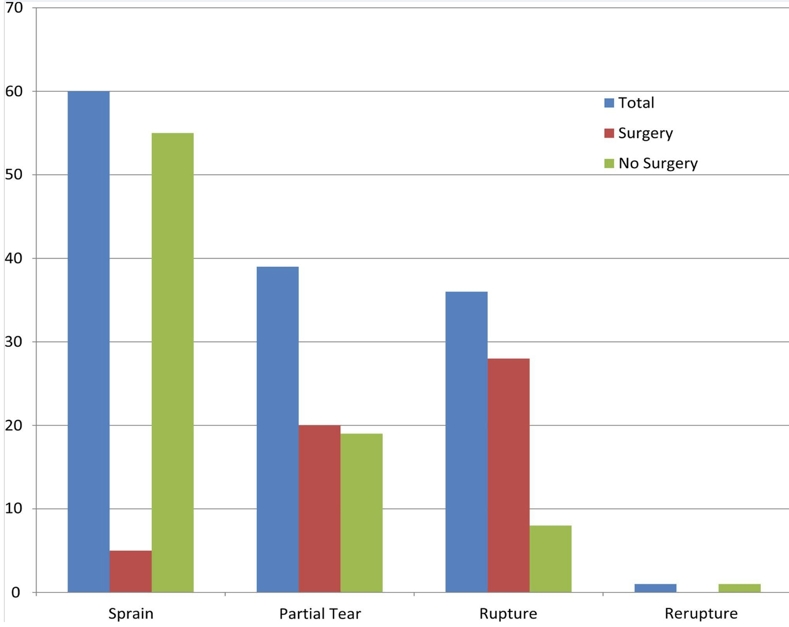

Zaremski assessed the total number of strains, partial tears, ruptures, and re-rupture in 136 patients with a UCL injury (see figure 6). Of the 136 patients, 53 were treated with surgery and 83 were treated conservatively. The greater the degree of injury, the more likely they were to receive surgery.The protocol used for patients not undergoing surgery in this research included a period of non-throwing action until the patient was symptom-free. During this time, there was no valgus strain on the elbow. Throwing activities were recommenced after six weeks and continued for a further six-week period. After a three month period, if symptoms still persisted, a referral for surgery was considered justified. This research study, however, didn’t report on the success of the conservative treatment and whether patients had to have surgery at a later date, or whether the patients who had surgery were able to return to pre-injury levels of sports participation.

Figure 6: Surgery versus non-surgical management of UCL injury(1)

Another research study found that 100% of patients (18 in total) with UCL injury were able to return to pre-injury levels having completed a non-operative rehabilitation protocol(4). In this study, the average reported loss of game time was just 0.64 games; this research is therefore very weak because it suggests that the 18 patients sustained very low-grade sprains of the UCL.

Researchers from Indiana University School of Medicine investigated the number of patients with UCL injury that was able to return to their sport(5). Thirty-one patients with a UCL injury participated in the study and followed a treatment protocol which consisted of two phases over a minimum of three months (see box). The results indicated that 13 patients were able to return to their sport after a minimum of three months, with an average of 24.5 weeks after initial diagnosis (ranging from 13-52 weeks). Of the 31 patients, 16 had acute injuries, and seven of these were able to return to sport pain-free. The volume of non-operative research into UCL injury is limited and is an area that warrants further investigation.

| Phase I | Phase II |

|---|---|

| Rest from throwing for three months. | This phase commences when movements are pain free. |

| Ice medial elbow for 10 minutes (4 x per day). | Discontinue splint or brace. |

| Long-arm splint or improved range of motion brace at 90° at night. Wear as needed to control pain during the day. | Progress upper extremity strength programme for all muscle groups. |

| Active and passive elbow movements for the flexors and pronators. | Commence throwing activities at three months. |

| Elbow hyperextension brace may be applied for lifting and throwing. |

There are a number of parameters involved in determining whether a patient is appropriate for UCL reconstructive surgery. These include the location of the UCL strain, severity of the injury and the timing of the injury (in or out of the season)(1). In addition, the age of the patient and the ability of the patient to continue participating in the throwing sport should also be assessed.

Summary

The UCL is frequently injured in adolescents and young adults involved in overhead throwing sports. Treatment is often conservative initially, but in certain cases may require surgical intervention. The majority of research is from a baseball background but much of the literature is transferable to other sports such as javelin, ultimate Frisbee and other throwing activities. However, more research is required to asses the non-operative protocols.Key points

- Ensure throwing actions are performed with correct technique and the movement is rehearsed repeatedly allowing for the development of the ulnar collateral ligament.

- Based on current research on non-operative patients, a period of three months should elapse before throwing activities are commenced again.

References

- Ortho J of Sports Med, Oct, 2017, 5, 10, 1 – 7.

- Sports Health, 2015, 7, 6, 511 – 517.

- J of Shoulder and Elbow Joint Surg, Oct, 2016, 25, 10, 1710 - 1716.

- J of Shoulder & Elbow Surg, Jan, 2000, 9, 1, 1-5.

- The Am J of Sports Med, 2001, 29, 1, 15-17.

You need to be logged in to continue reading.

Please register for limited access or take a 30-day risk-free trial of Sports Injury Bulletin to experience the full benefits of a subscription. TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

TAKE A RISK-FREE TRIAL

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.