You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

From Sampling to Specialization: A Smarter Pathway for Youth Athletes

Youth sports have quietly been popularizing a dangerous trend: the sooner you start focusing on early sport specialization, the greater your chances of going professional. Jarred Marsh challenges this stance and provides clinicians with guidance on injury risks for athletes specializing early.

Australia’s Ashleigh Barty poses as she celebrates winning the final against Danielle Collins of the U.S. with the trophy. She also played professional cricket for the Brisbane Heat. REUTERS/Loren Elliott.

The concept of early sport specialization (ESS) isn’t new, and it’s not a hard idea to sell to coaches, parents, and youth athletes. Focusing on one sport all year round will help you hone key developmental skills and keep you ahead of your peers. Sadly, that narrative has significant pitfalls that can impact a youth athlete’s health, well-being, and – ironically, their chances of elite sport success.

Researchers continue to examine ESS as a pathway for youth athletes to achieve senior elite success. Contrary to the hopes of many aspiring athletes (and their supportive parents), ESS increases the risk of injury and burnout rather than improving long-term performance outcomes(1). However, clinicians play a vital role in helping youth athletes stay healthier, participate longer, and ultimately enjoy their sports.

"... acute and overuse injury risk increases with higher degrees of ESS."

What is Early Sport Specialization?

The definition of sport specialization in both an academic and applied setting refers to three common points:

- Participation in one main sport,

- Year-round training of that one sport (longer than eight months),

- Avoiding participation in other sports in favor of the selected sport(2).

Practitioners refer to sport specialization as “early” when it occurs in a child’s pre-pubescent phase of development (before puberty). Definitions may vary slightly between coaches and academics, which is why clearer, more standardized criteria are needed when defining ESS(3). However, even with varying definitions, the pattern is consistent: the earlier a youth athlete commits to one sport and trains year-round, the greater the risk of injury and burnout(1,4,5).

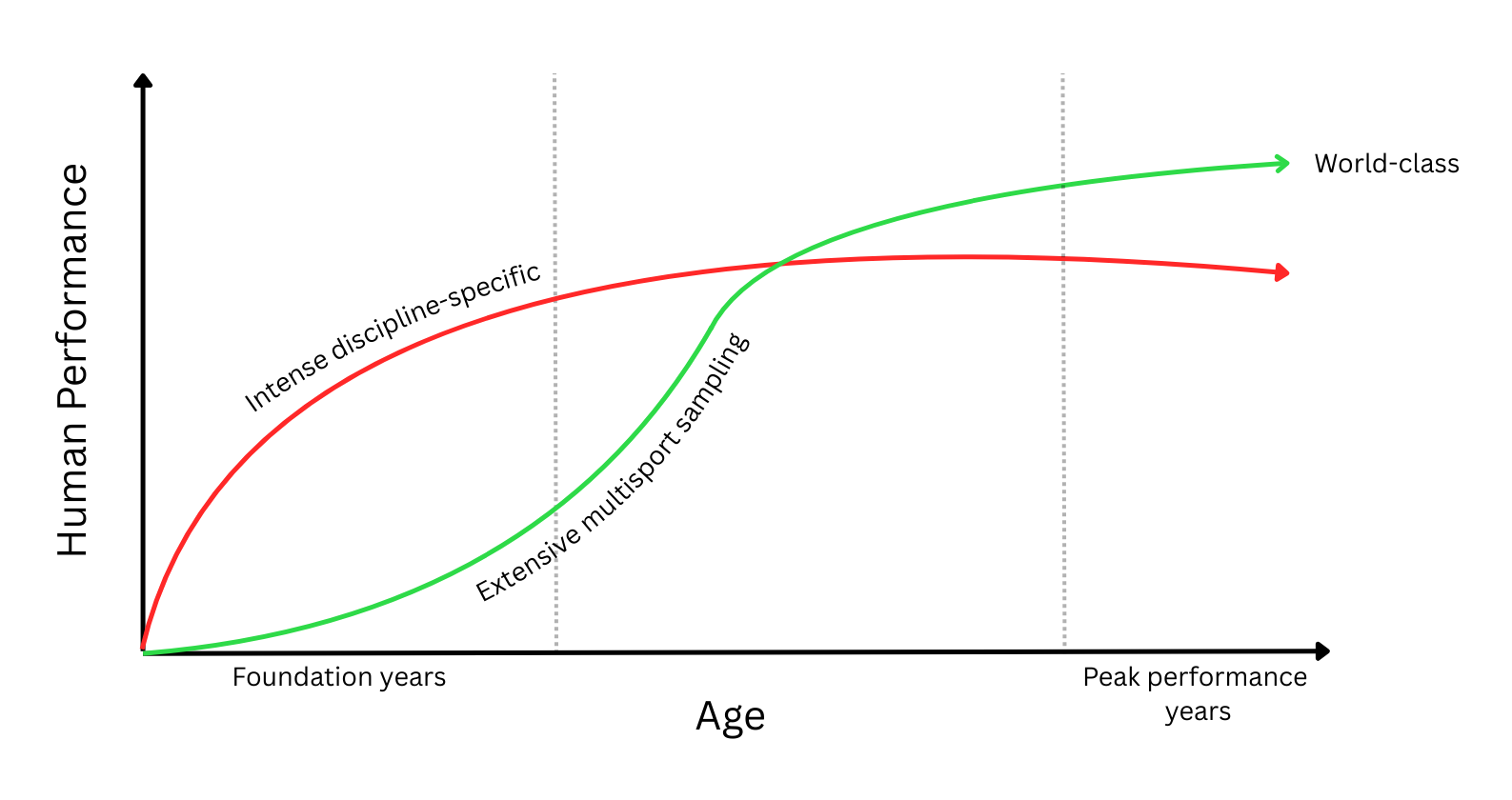

What Elite Sport Development Pathways Look Like

To best understand elite sport development, it’s important to first look at elite senior athletes and retrospectively analyze what they did in their early years of sporting development. A match-paired analysis of 83 international medalists (including Olympic and World Champion athletes) and 83 matched non-medalists found that medalists did not specialize early. Their development pathways involved multiple sports participation and mixed training methods, thereby challenging the ESS narrative(6).

Diving deeper, researchers conducted a large meta-analysis of several studies that examined nearly 800 top sports professionals, finding that when compared to national-class athletes, world-class athletes:

- Delayed their specialization,

- Accumulated less training volume in their main sport of choice during adolescence,

- Engaged in more practice of other sports during adolescent development(7).

Similarly, a systematic review conducted by researchers at the University of California examined elite, professional, and Olympic athletes. They found that youth multisport engagement leads to better performance outcomes in later years highlights a strong correlation between broad athletic exposure in childhood and later focused specialization(1). To be certain, this does not mean that all elite sportspeople participated in several sports during childhood. However, it does highlight a strong correlation between broad athletic exposure in childhood and later focused specialization(1,7).

This, therefore, begs the question: Does ESS align with elite development pathways and set youth athletes up for successful sporting careers?

Early Specialization and Injury Risk

The most consistent finding in the plethora of research studies focusing on early specialization isn’t about improving performance but rather about the increased risk of injury in youth sports populations. Injury risk is significantly reduced in youth athletes who delay ESS until after adolescence(1). Furthermore, acute and overuse injury risk increases with higher degrees of ESS(5). This also included a higher risk of injury in female youth athletes than their male peers.

A clinical report by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) on sport specialization and intensive training highlights concerns about overuse injuries, overtraining, and burnout among youth athletes. The report also provides recommendations for avoiding early, intensive, year-round specialization for youth athletes(4).

When considering the root cause of this increased injury risk, it is difficult not to question the repetitiveness of year-round training in the same movement patterns, monotonous training loads, limited training variation, reduced sleep and recovery, all during periods of peak growth and possibly competition congestion(4,8). These injuries inherently cause developmental breakdown, as athletes are no longer able to train or compete.

In contrast, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) consensus statement on youth athletic development promotes the development of healthy, resilient youth athletes through evidence-informed practice that avoids inappropriate training loads and supports sustainable development(9).

Clearly, the best development pathways are the ones that keep youth athletes available to train consistently, learn, and improve gradually.

Table 1: Common overuse injuries in young athletes(4).

| Injury | Common Locations |

| Apophysitis | Calcaneus, tibial tuberosity, medial epicondyle |

| Bone stress injury (stress reaction, stress fracture) | Tibia, metatarsals, lumbar spine |

| Tendinopathy | Patellar tendon |

| Epiphysiolysis | Proximal humerus, distal radius |

| Patellofemoral pain syndrome | Anterior knee |

| Osteochondritis dissecans or Panner’s disease | Capitellum |

Burnout and Dropout

Aside from the increased risk of injury, another major cost of ESS is psychological. When sport becomes too rigid too early – constant evaluation, heavy coach-imposed structure, pressure, and identity tied to performance – burnout becomes a reality.

A public health review conducted by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison discussed the impact of ESS on burnout. It was noted that ESS has a direct effect on youth sports and that associated youth sport dropout is substantial(10). A commonly cited reason for this dropout was the reported “pressure” that youth athletes feel, with dropout and burnout closely linked to intensive training and specialization cultures.

It is possible to be pessimistic about these reports. Still, it is hard not to acknowledge the core takeaway: by building narrow development pathways that increase pressure, reduce enjoyment, and tie identity to result-based outcomes, parents, coaches, and practitioners cannot be surprised when youth athletes choose to stop participating. They need to monitor aspects such as training volume, monotony of training, and recovery, and ensure that children experience sport as both play and practice.

Table 2: Risk and protective factors for burnout(4).

| Risk Factors | Preventative and Protective Factors |

| Pressure or extrinsic motivation | Intrinsic motivation |

| Perceived stress | Supportive parental relationship |

| Prioritizing short-term goals | Long-term athlete development models |

| Perfectionism | Higher levels of autonomy, optimism, and mental toughness |

| Focus on performance outcomes from peers, coaches, or parents | Prioritization of effort and intrinsic goals over extrinsic goals |

| Overscheduling and high chronic training loads | Adequate rest and breaks from participation |

| Intrateam conflict | |

| High chronic training loads |

The Multisport Approach

A multisport approach underpins wellness in youth athletes. But how does it impact actual sporting performance? When clinicians view performance as robust and injury-resilient, athletes who are consistently available to train and practice over time, they must consider:

- A broader physical literacy toolbox

When coaches and parents expose children to multiple sports at an early age, they experience playing different positions, encounter varied coordination challenges, and are required to make decisions at different speeds. Development of this broad base can support adaptability later in their development as sport-specific demands increase. For example, world-class athletes often have more multisport exposure in their early developmental years(7). - Load variation and tissue adaptation

Different sports place different loads on the body. High-impact, plyometric-based sports like basketball will result in different physical adaptations than low-impact sports like swimming. Multisport participation allows variation in these loading patterns and may help reduce repetitive stress patterns and the risk of overuse injuries, especially in year-round single-sport athletes(5). - Motivation and longevity

What if long-term participation is more important than long-term specialization? If a youth athlete can remain injury-free, stay healthy, and enjoy their sports, they will inevitably train longer, learn more, and successfully reach later developmental windows. Delaying specialization enhances multisport engagement, which improves performance outcomes(1).

"...allow for multisport exposure in earlier years..."

Caveat: Early Specialization can be Helpful - Sometimes

There is a nuance to this discussion. Some sports, such as long-distance running, require a high degree of technical proficiency. This proficiency stems from spending more time developing the necessary skills to perform optimally and, therefore, requires greater investment at earlier ages. The report by the American Academy of Pediatrics acknowledges that early specialization in specific sports may be more common in these select sports. However, it is still imperative for family members and coaches to maintain close observation of athletes to manage the risk of burnout or injury(2,4).

The takeaway for coaches and parents alike is:

- Earlier specialization does not always mean better outcomes.

- Avoid using the exception to the rule as the rule.

- If early specialization is required for a sport, manage all risk factors continuously (provide clear off-season breaks, plan regular recovery periods, carefully monitor the athlete)(2,9).

Clinical Implications

Using these evidence-aligned, coach-friendly principles may not only reduce the risk of injury and burnout, but also improve long-term performance outcomes in multisport athletes:

- Prioritize long-term availability over short-term gains

Prioritizing performance in a U13 tournament is not the same as long-term development for future senior elite athletes. Many world-class athletes were not frontrunners in their adolescent years (see figure 2)(7). - Build a broad base, then narrow (when appropriate)

Building a youth athlete’s confidence, general sporting skills, and broad athletic base in adolescence is vital to sports performance in later years. Delay focusing on specific sports until the athlete is ready(7). - Avoid year-round monotony

Training year-round in a single sport is a common denominator for injury risk and burnout. Planning appropriate breaks in training, as well as training variation, is an important aspect of long-term success(4,5). - Training hours < Athlete age principle

When an athlete’s weekly training hours (including free play) exceed their age (in years), their injury risk increases significantly(5). - Allow time for the athlete to “play”

Unstructured, peer-led play not only allows youth athletes to step away from the stress and pressure of sport but also creates positive relationships with sport and physical activity. These are central to maintaining lifelong participation(9,10).

Summary

The argument for multisport participation over ESS is a fundamental one. Across multiple areas of evidence, elite sport pathways are broader in the early years, and youth athletes at risk of injury and burnout are pushed into narrow, year-round, single-sport training too early.

The goal, as parents, coaches, and practitioners, is to ensure that youth athletes experience development that lasts. Building robust, resilient, and motivated youth athletes is easier than it seems – allow for multisport exposure in earlier years and then, when the time is right for the athlete, transition safely to specialization.

References

1. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022 Nov 4;10(11):23259671221129594.

2. J Athl Train. 2021 Mar 31;56(11):1239–1251.

3. Front. Sports Act. Living, 2020; 2:596229.

4. Pediatrics. 2024; 153 (2): e2023065129.

5. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020 Jun 25;8(6):2325967120922764.

6. J Sports Sci. 2017 Dec;35(23):2281-2288.

7. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2022 Jan;17(1):6-29.

8. Clin J Sport Med. 2014 Jan;24(1):3-20.

9. Br J Sports Med. 2015 Jul;49(13):843-51.

10. J Athl Train. 2019 Oct;54(10):1013–1020.

11. Science 390,eadt7790 (2025).

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.