You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Psychological Flexibility in Rehabilitation

Injury rehabilitation demands that clinicians use a psychologically flexible approach to support athletes navigating the often complex mental challenges. Carl Bescoby explores the science behind psychological flexibility and provides practical strategies for helping clinicians foster psychological flexibility in the rehabilitation to help individuals navigate recovery more effectively.

Chennai Super Kings’ Ruturaj Gaikwad receives medical attention after sustaining an injury REUTERS/Stringer

Introduction

Athletes may frame rehabilitation as a purely physical process focusing on strength, mobility, and tissue healing. However, there is increasing emphasis on the role of psychological flexibility (PF) in injury recovery. Psychological flexibility is rooted in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), a third-wave cognitive behavioral approach(1,2). It refers to the ability to adapt, remain engaged in meaningful actions, and persist despite discomfort. For clinicians, integrating PF into rehabilitation practice can enhance patient adherence, pain management, and emotional resilience.

“Psychological flexibility can be a game-changer in rehabilitation.”

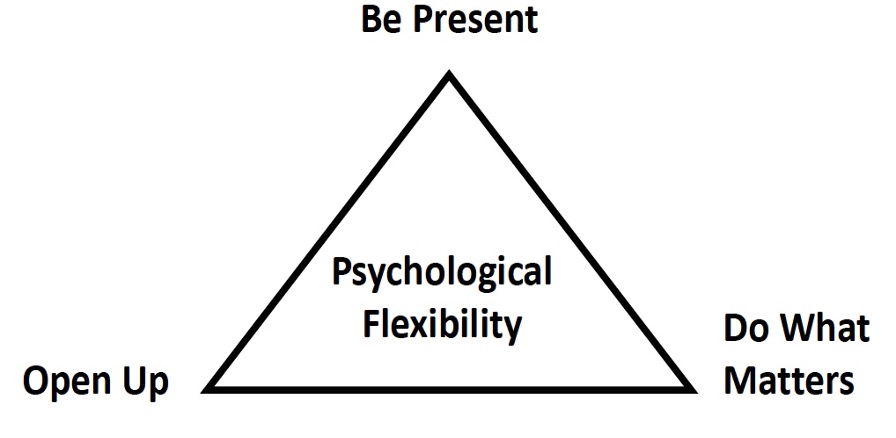

Psychological Flexibility

Psychological flexibility is the capacity to be open with thoughts, feelings, and emotions and for these not to influence the pursuit to change or persist with behavior that is guided by an athlete’s values and goals (see figure 1). It is the ability to remain open to experiences, including discomfort, while still taking actions aligned with one’s values. It involves six interrelated processes: acceptance, cognitive defusion, present-moment awareness, self-as-context, values, and committed action. These processes help injured athletes build resilience, improve adherence to rehabilitation programs, and enhance pain tolerance. For example, PF lowers pain-related distress and improves rehabilitation engagement and psychological readiness for return to sport. In contrast, psychological rigidity—characterized by avoidance, over-identification with negative thoughts, and disconnection from values—can significantly hinder the recovery process. Rigid athletes may avoid rehabilitation exercises due to fear of pain, catastrophize setbacks, and experience reduced motivation(3). Recognizing these patterns early allows clinicians to intervene effectively and shift the focus toward more adaptive behaviors.

Scientific Evidence

Higher PF is associated with lower pain interference, better injury recovery, and improved return to sport readiness. For example, researchers at the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College in London found that individuals with greater PF experienced less psychological distress related to chronic pain(4). Similarly, there is a strong link between PF and rehabilitation adherence in athletes recovering from musculoskeletal injuries(5). Furthermore, PF is effective within sports and rehabilitation settings(6,7). From a neuroscience perspective, PF enhances emotional regulation by modulating activity in the prefrontal cortex and amygdala, reducing fear responses. Cognitive defusion techniques help shift pain perception by disrupting maladaptive thought patterns. Values-based action activates reward pathways in the brain, reinforcing motivation to stay engaged in rehabilitation. Understanding these mechanisms helps clinicians tailor interventions supporting mental and physical recovery.

“Athletes may frame rehabilitation as a purely physical process…”

Clinical Implications

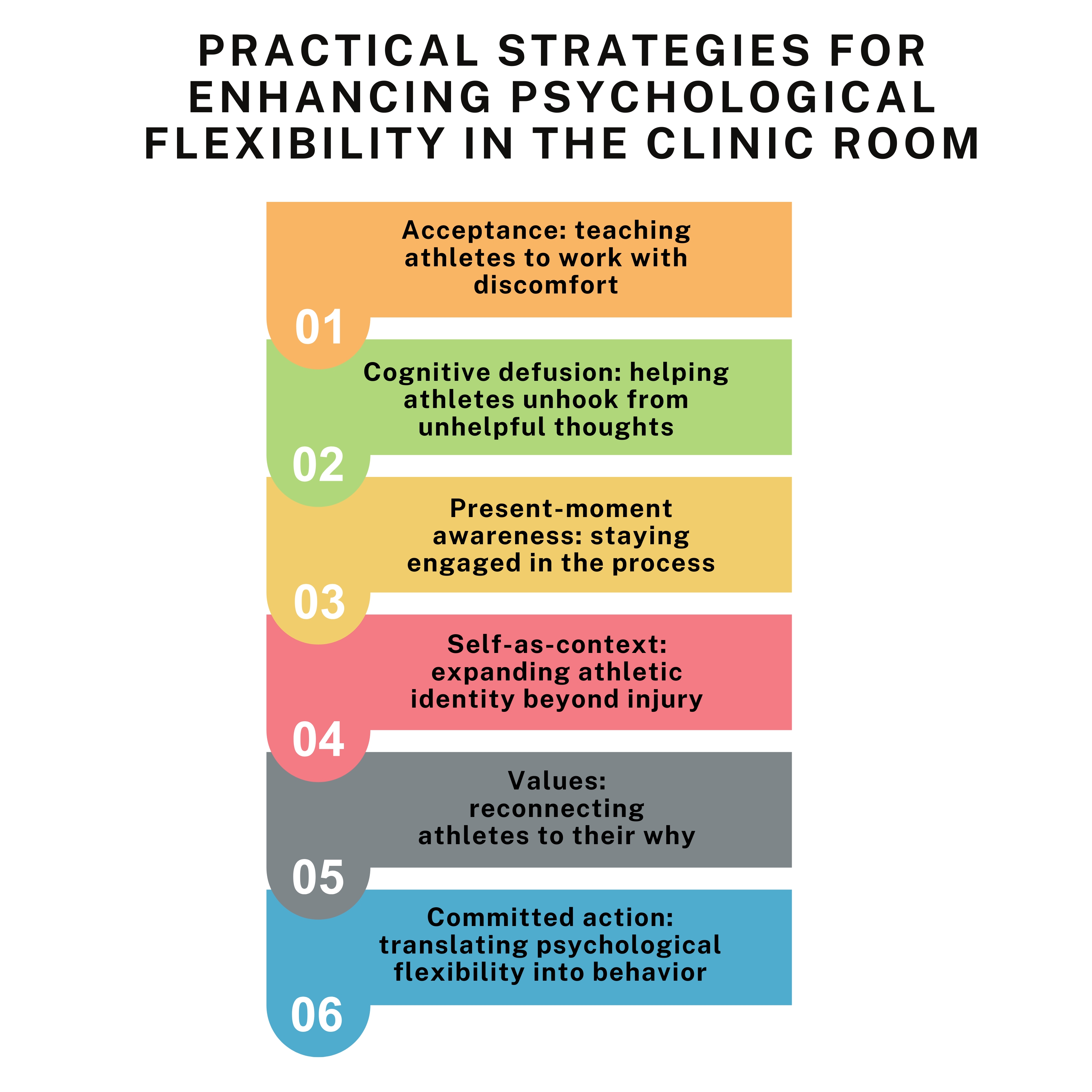

Clinicians can integrate psychological flexibility into their practice by integrating strategies such as acceptance, cognitive defusion, present-moment awareness, self-as-context, values clarification, and committed action (see figure 2). While these strategies may seem quite novel and unusual to clinicians, their practical application can be simplified and embedded in the clinic room effectively. These strategies build resilience, reduce avoidance behaviors, and stay engaged in their recovery journey.

1. Acceptance: teaching athletes to work with discomfort

Acceptance involves making space for discomfort rather than resisting it. Clinicians can help athletes reframe pain as a natural part of recovery rather than a signal of failure. One useful metaphor is quicksand—the more you struggle against it, the deeper you sink. The idea here is to drop the struggle as this often costs more in the long term. Exposure-based techniques, such as graded activity exposure, help athletes gradually engage with movements they may fear, reducing avoidance behaviors. Thus, it helps individuals accept and make room for discomfort along the way.

2. Cognitive defusion: helping athletes unhook from unhelpful thoughts

A common experience for athletes going through rehabilitation is the experience of unhelpful thoughts questioning the rehabilitation process. These thoughts can become destructive if left unmanaged, leading to difficult feelings, emotions, and unhelpful behaviors(8). Cognitive defusion teaches athletes to separate themselves from distressing thoughts. Rather than identifying with negative self-statements like "I’ll never recover," athletes can learn to say, "I’m having the thought that I’ll never recover." Repeating distressing thoughts aloud or visualizing them as passing clouds can help reduce their emotional impact. Encouraging athletes to view challenges from a future perspective also aids in breaking thought patterns that limit progress.

3. Present-moment awareness

Often connected to the challenges athletes face with negative thoughts, feelings, and emotions, they face the challenges of staying present and engaged in rehabilitation. Mindfulness techniques, such as mindful movement and breath-focused exercises, can be useful strategies to keep athletes present, grounded, and engaged in their rehabilitation journey. Teaching athletes to pay attention to body sensations during exercises can enhance neuromuscular control and reduce anxiety about reinjury. There is also growing evidence supporting the use of neuromuscular training on physical fitness in sports(9). Furthermore, attending to and being open to the injury experience can help athletes accept their thoughts and feelings without judging or trying to change them. This would enable individuals to shift attention to rehabilitation instead of becoming preoccupied with their psychological reactions.

4. Self-as-context

As a PF concept, self-as-context is more challenging to translate for clinicians who lack the psychological underpinning. Injury can trigger identity crises, particularly in competitive athletes who closely tie their self-worth to performance(10). Therefore, self-as-context encourages athletes to view themselves beyond their current physical limitations to foster resilience and stability in how they view themselves. For example, instead of athletes viewing themselves as an injured athlete, they may acknowledge that injury is something they are experiencing right now, but it does not define who they are or their worthiness. Exercises such as narrative reconstruction—where athletes rewrite their injury story to include themes of growth and learning—can help shift their perspective from loss to adaptation.

5. Values

Values serve as a compass, guiding behavior even in difficult moments(11). Values are not the same as goals, as athletes continue to strive towards values- not something they can tick off and complete. Clinicians can help athletes identify what truly matters beyond just returning to sport. For example, asking questions like “Why is being an athlete so important to you” or "What kind of teammate do you want to be during rehab?" can shift the focus from short-term frustration to long-term growth. Thus, connecting rehabilitation activities to deeply held values, such as perseverance or courage, enhances motivation and engagement.

6. Committed action

The final strategy to support PF in rehabilitation settings is committed action. This involves taking purposeful steps (being value-driven) despite challenges (opening up to and making room for discomfort). Clinicians can use implementation intentions to create structured action plans. For example, an athlete may incorporate a committed action such as "When I feel pain, I will use a relaxation technique and continue with my modified exercises." This would enable the athlete and clinician to address any avoidance behaviors through gradual exposure and setting small progressive goals to help athletes ultimately maintain momentum in their rehabilitation. There are often many moments during the rehabilitation journey where athletes must show up when they feel uncomfortable, such as when fear shows up when reengaging in activity for the first time. Committed action enables individuals to make room for this discomfort.

Practical Framework

Having outlined the six strategies for enabling PF in rehabilitation settings, the hope is that these could be implemented without the foundational knowledge that underpins psychological interventions. However, integrating PF principles requires recognizing psychological rigidity early and implementing brief, effective interventions. Here, clinicians can introduce PF techniques seamlessly within rehabilitation sessions without extensive psychological training. Simple techniques, such as brief mindfulness exercises, values-based goal-setting, and cognitive defusion strategies, can be incorporated into existing rehabilitation protocols. Furthermore, education plays a crucial role in applying PF principles effectively. Clinicians should consider providing psychoeducation to athletes, helping them understand how their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors influence recovery. This could be done by encouraging the athlete to access psychological resources such as workbooks or tools to support their psychoeducation. Clinicians can encourage reflective journaling or guided discussions about injury-related fears and frustrations, further enhancing self-awareness and adaptability.

It is equally important for clinicians to train in PF concepts. When the broader support network reinforces psychological flexibility, athletes receive consistent messaging that normalizes emotional struggles and setbacks. This consistency fosters a more adaptive rehabilitation environment, reducing fear and avoidance tendencies. For example, setbacks are a natural part of rehabilitation, and normalizing them can prevent psychological rigidity. Clinicians can reframe setbacks as opportunities for growth rather than failures. Athletes who experience flare-ups or missed progress benchmarks can be encouraged to view these moments as temporary and to realign their efforts with their values. Structured debriefs after setbacks can reinforce psychological resilience and commitment to the process.

“Clinicians can reframe setbacks as opportunities for growth rather than failures.”

Conclusion

Psychological flexibility can be a game-changer in rehabilitation. By integrating acceptance, cognitive defusion, present-moment awareness, self-as-context, values, and committed action, clinicians can enhance athlete resilience, pain tolerance, and rehabilitation engagement. Ultimately, physical recovery is not just about the body but the mind’s ability to stay adaptable, engaged, and committed.

References

1. What is ACT. 2004, 3-29. Boston, MA: Springer US.

2. Behaviour research and therapy. 2006, 44(1), 1-25.

3. J for Adv Sport Psych in Research. 2024, 4(1), 4-20.

4. American psychologist. 2014, 69(2), 178.

5. ACT Rehab Adherence Sport Injury. 2014, Hofstra University.

6. J of Clin Sport Psych. 2016, 10(3), 192-205.

7. J of Sport and Ex Psych. 2014, 36(3), 281-292.

8. J of athletic training. 2015, 50(1), 95-104.

9. Front Physiol. 2022, 13:939042.

10. J of Loss and Trauma. 2019, 24(1), 17–30.

11. J of Sport Psych in action .2024, 15(3), 125-137.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.