You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

The Labral Labyrinth: SLAP injuries – Part 1

SLAP injuries occur most commonly with repetitive motion from overhead sports or traumatic injury. Kelly Mackenzie takes a deep dive into the anatomy, assessment, and management of SLAP lesions to ensure that athletes receive the best care options.

Serbia’s Adriana Vilagos in action during the women’s javelin throw. Heiko Junge/NTB.

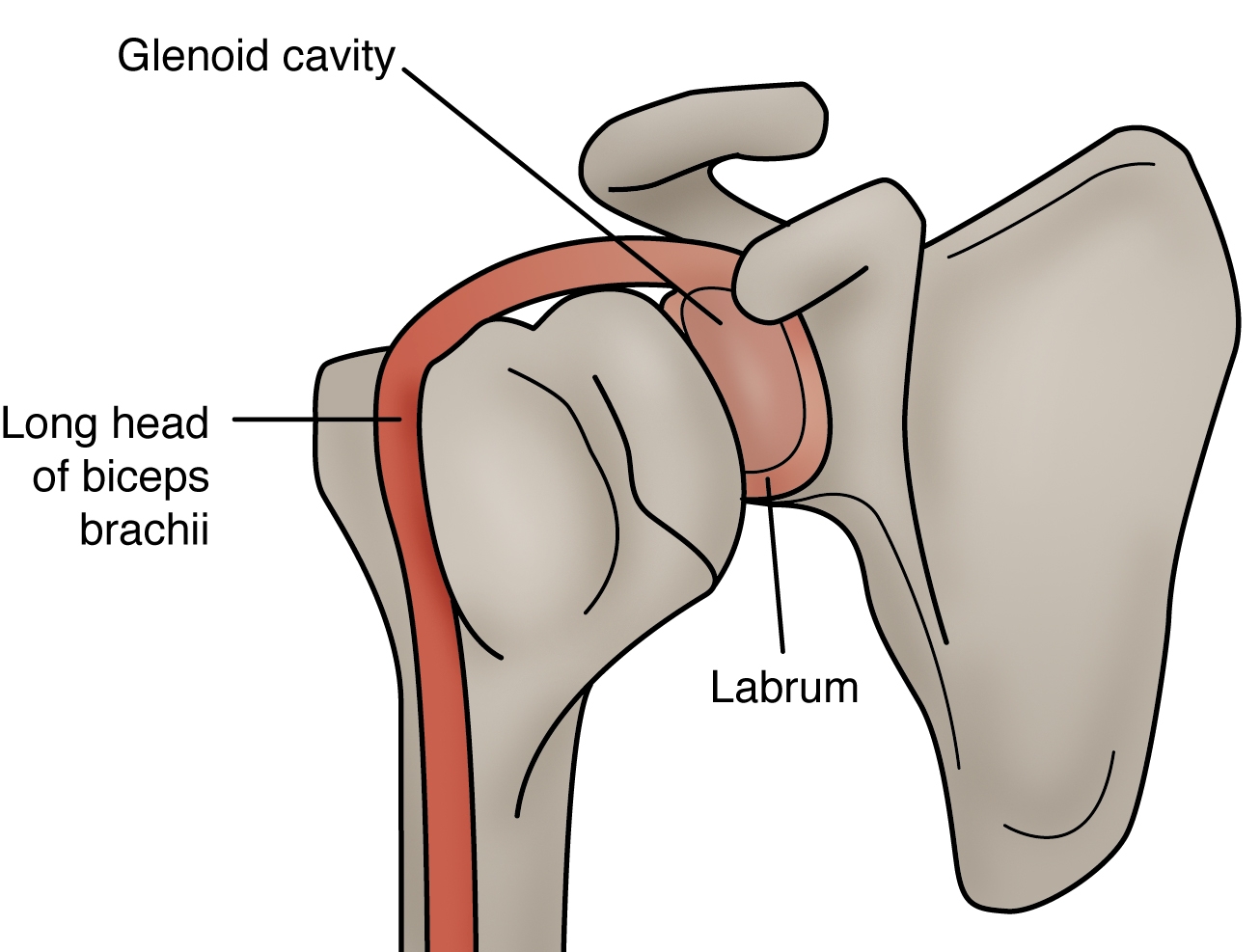

Shoulder pain and injury are common in the general and athletic populations. The glenohumeral joint is a very shallow but mobile joint that acquires most of its stability from the surrounding soft tissue structures, including the glenoid labrum. Injury to the superior glenoid labrum where the long head of the biceps tendon inserts is known as a SLAP (superior labrum anterior to posterior) injury or SLAP tear.

SLAP injuries occur most commonly with repetitive motion from overhead sports or from traumatic injury, such as a fall on an outstretched arm, where both mechanisms represent a biomechanical mismatch between force and fixation. The presentation is usually deep shoulder pain that may present as bicep pathology.

Clinicians typically require magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to evaluate the superior labrum and assess the condition of the biceps tendon. Management can be either non-surgical or surgical, depending on factors such as the patient’s age, activity demands, symptom severity, and the presence of shoulder instability.

Anatomy

Glenohumeral Joint

The glenohumeral joint (GHJ) is a shallow ball-and-socket joint. The ball of the humeral head fits into the glenoid fossa of the scapula. In reality, the glenoid fossa looks more like a saucer, covering only a third of the surface area of the humeral head. Due to the shallow glenoid fossa, the GHJ is reliant on other static and dynamic structures to offer stability. The static stabilizers consist of the glenohumeral ligaments, the glenoid labrum, and the capsule, while the rotator cuff and scapular muscles offer dynamic stability. What the joint lacks in stability, it makes up for with its extensive mobility(1).

Labrum

The fibrocartilaginous glenoid labrum deepens and widens the area that receives the humeral head by 75% superior-inferiorly and 50% anterior-posteriorly(1). It attaches directly to the glenoid and has a unified appearance. It can sometimes be meniscoid and hang over the edge, which may be mistaken for a tear on a scan. However, this is a normal anatomical variant in 1% of patients(2). The Buford complex is found in approximately 1.5% of patients and is often benign and a normal anatomical variant. It is characterized by a bare area of the anterior superior labrum and an associated thickened middle glenohumeral ligament (MGHL)(3). The labrum serves as both a cushion and a stabilizer for the humeral head and provides attachment points for the capsule, glenohumeral ligaments, and the long head of the biceps. Furthermore, the labrum acts like a rubber ring in a suction cup, which helps to create a negative pressure seal that holds the humeral head snugly in place. It receives its blood supply from the capsule and periosteal vessels of the glenoid, with the anterior superior labrum having the poorest blood supply(2).

Biceps Tendon

About 50% of the long head of the biceps tendon fibers attach to the superior labrum, and the other 50% attach to the supraglenoid tubercle. Most commonly, the bicep tendon attaches to the labrum in the 12 o’clock position. It traverses the GHJ, where its blood supply is at its poorest. It then exits through the bicipital groove and continues down the arm(4). It provides dynamic anterior and superior stability to the humeral head during movement, especially during overhead movements, and acts as a barrier to subluxation. This makes this area vulnerable in overhead and traction-based activities(2).

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

SLAP injuries are fairly uncommon and account for only 5% of all shoulder injuries. It is usually found in the dominant shoulder of overhead athletes, and glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) is a risk factor(2). Contact sports, such as rugby, increase the risk of injury due to certain factors, including the shoulder position when diving for a try, falling on the field, and playing in front-row positions where the shoulder is most vulnerable(5,6).

“The accurate diagnosis and management of SLAP tears demand a nuanced approach.”

Mechanism of Injury

The “peel-back mechanism” occurs when the long head of the biceps pulls on the superior glenoid labrum with shoulder and elbow movements. When the shoulder is in the extreme ranges of abduction and external rotation, there is a torsional force of the biceps-labral anchor. This can lead to superior-posterior labral detachment. A sudden forceful traction from above the head and loaded activity (such as a fall on an outstretched arm) where the bicep is tensed or bracing, can also cause an avulsion of the labrum to its superior attachment site. Contributing factors may involve the tightness of the posterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL), which causes a posterior shift in the glenohumeral contact point and elevates shear forces on the superior labrum. SLAP lesions further increase strain on the anterior band of the IGHL, thereby compromising shoulder stability(2).

Classification

In the 1990s, clinicians at the Southern California Orthopedic Institute defined four types of SLAP tears based on arthroscopic investigation(7). More recently, in 2023, South African clinicians added six additional classifications (see table 1). However, there is wide variability in the inter- and intra-rater classification of SLAP tears(8).

Table 1: Classification of SLAP injuries(8)

| SLAP Type | Key Features | Additional Notes |

| Type I | Degenerative fraying at the free edge of the labrum and bicep. | Attachment to the superior glenoid remains intact. |

| Type II | Attachment to the superior glenoid remains intact. | Cartilage is absent at the site of avulsion. |

| Type III | Bucket-handle tear of the labrum. | LHBT insertion is preserved; rare variant. |

| Type IV | Bucket-handle tear that extends into the LHBT. | Often associated with anterior instability. |

| Type V | Type II tear pattern with added anterior shoulder instability. | Involves anteroinferior labral extension. Also known as a Bankart lesion. |

| Type VI | Tear with large superior labral flaps. | LHBT insertion remains attached; incidence is unclear. |

| Type VII | Type II pattern with injury to the middle and inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL). | Seen in cases of complex shoulder instability. |

| Type VIII | Type II pattern with adjacent cartilage damage near the bicipital footplate. | Extends into the superior glenoid cartilage. |

| Type IX | Circumferential tear. | |

| Type X | Type II plus posterior inferior extension. | Also known as a reverse Bankart lesion. |

The incidence of SLAP lesions varies across the evidence, with type I accounting for approximately 9.5–21%, type II being the most common at 41–55%, type III ranging from 6% to 33%, and type IV reported in 3–15% of cases. Clinicians observe Type II SLAP lesions most frequently during arthroscopy, and a comparable prevalence is typically seen on MRI(9).

Presentation

The main complaint with a SLAP lesion is vague, deep shoulder pain, with some patients describing a memorable popping sensation during a past overhead activity. They may point to an area of deep pain (anterior or posterior) somewhere between the acromion and the coracoid process(2). There can be a delay between the initial injury and the onset of symptoms. Pain is generally intermittent and is felt during overhead activity, lying on the affected arm (not necessarily at night), and with quick whipping movements, such as throwing a cricket ball or hitting a squash ball. Furthermore, athletes may present with clicking and locking (with or without pain), loss of scapular and rotator cuff strength and stability, and a decrease in internal shoulder rotation. This often leads to reduced performance in muscular power and throwing speed, accompanied by diminished precision and control, particularly impacting athletes who rely heavily on overhead or throwing motions, such as baseball pitchers, tennis players, and swimmers.

“A thorough clinical examination should be tied to a subjective history.”

Diagnosis

A thorough clinical examination should be tied to a subjective history. While no single provocative test is definitive for diagnosing SLAP tears, a combination of tests can be useful in making a diagnosis. The history and patient presentation should give a clinician a high index of suspicion, and they should use clinical tests to add confidence to their diagnosis(10).

Clinicians should assess scapular alignment and any signs of muscle wasting, particularly around the shoulder girdle. Palpation over the bicipital groove may provoke tenderness, suggesting involvement of the long head of the biceps tendon, but is not diagnostic of a SLAP tear. The biceps tendon may be a secondary pathology to the SLAP injury. During assessment of shoulder range of motion (ROM), a clicking or popping sensation may be reproduced during overhead movements, but this is not diagnostic of a SLAP tear as a stand-alone finding(11). Clinicians should note the changes in internal rotation range and total rotational range and compare them to those on the opposite side. Up to 85% of patients with SLAP lesions demonstrate apprehension during testing(12).

Neurovascular and Special Testing

Neurological examination may reveal supraspinatus and infraspinatus atrophy, potentially indicating suprascapular nerve involvement. There are over 26 tests in the literature that clinicians use to diagnose or rule out SLAP tears. However, there is no single maneuver that can accurately diagnose SLAP lesions (see table 2)(14).

Table 2: SLAP Special tests(12-16)

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | Notes |

| Relocation Test | 51.6% | 52.4% | |

| Yergason’s Test | 12.4% | 95% | Highest specificity for SLAP. |

| Compression-Rotation Test | 24% | 78% | Best positive likelihood ratio in meta-analysis. |

| Speed’s Test | 37% | 62% | Large variance in studies assessing sensitivity. |

| Passive Distraction and Active Compression Tests (Combined) | 70% | 90% | Improved results in combination. |

| Passive Compression Test | 82% | 86% | Reported as clinically useful, but only has single study validation. Caution is warranted. |

| Modified Dynamic Labral Shear Test | 78% | 51% | May detect labral tears broadly; possibly sensitive for SLAP. |

| Biceps Load II Test | 55% | 53% | Only test with utility in SLAP-only cases. |

Standard radiographs are often unremarkable in suspected SLAP lesions. MRI, complemented by an MR arthrogram, is the imaging gold standard when clinical suspicion remains high, with a sensitivity for SLAP lesions of around 50%. However, specificity reaches up to 90% and is enhanced with the use of an arthrogram. The presence of a paralabral ganglion cyst, particularly in the spinoglenoid notch, is highly suggestive of a labral tear(17).

The accurate diagnosis and management of SLAP tears demand a nuanced approach. These injuries, often resulting from trauma or repetitive overhead activities, can be elusive, with standard assessments and imaging sometimes failing to detect them, leading to persistent shoulder discomfort. A comprehensive clinical evaluation remains paramount and special tests on their own don’t provide diagnostic accuracy, while combining them improves accuracy marginally(13). However, even combining tests remains disputed(15). Part two will discuss the management options and provide clinicians with clarity on the best approach to helping athletes recover.

“The main complaint with a SLAP lesion is vague, deep shoulder pain…”

References

- Brukner & Khan’s clinical sports medicine (5th ed.). 2017: 342-346.

- Orthobullets. (n.d.). SLAP lesion. Retrieved May 25, 2025, from www.orthobullets.com/shoulder-and-elbow/3053/slap-lesion?section=bullets

- Radiopaedia.org. (n.d.). Buford complex. Retrieved May 25, 2025, from radiopaedia.org/articles/buford-complex.

- J Shoulder Elbow Surg.1994, 3(6), 379–385.

- Clin J Sport Med. 2007 Jan; 17 (1): 1-4.

- Phys Ther Sport. 2004 Feb. 5(1): 44-50.

- Arthroscopy. 1990 Dec; 6(4): 274-279.

- S Afr J Rad. 2023;27(1).

- J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003; 12(6), 579–585.

- Arthroscopy. 2015 Dec; 2456-246.

- J Athl Train. 2011; 46 (4): 343–348.

- Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2010; 2(2).

- Br J Sports Med 2012 Nov; 46(14):964-78.

- Am J Sports Med. 2006 Feb; 34(2).

- J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012 Jan; 21(1): 13-22.

- Am J Sports Med. 2017 Mar;45(4):775-781

- Open Orthop J. 2018. 12: 314.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.