You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Injury Patterns in Rock Climbing

Rock climbing places unique demands on the body, combining high finger loads with complex full-body movement. Collin Filley unpacks the common injury patterns for clinicians.

Sasha DiGiulian climbs the Platinum route on El Capitan in Yosemite National Park, California, USA on November 7, 2025. // Pablo Durana / Red Bull Content Pool.

Rock climbing is one of the fastest-growing sports worldwide. The expansion of indoor facilities has made what was once a sport for intrepid athletes accessible to casual weekend warriors. Now an Olympic event, climbing participation increased by 7.1% from 2019 to 2021 and continues to trend upward(1). Every sport has inherent risks of overuse and traumatic injuries. Still, climbing has unique risks compared to other activities, primarily due to the height and the extreme stress placed on the fingers. While athletes and facilities both take precautions to avoid injury by modifying the environment and using safety equipment, climbing has a higher injury rate than in years past, likely due to lower barriers to entry today.

There are several disciplines within climbing that sports medicine clinicians should be familiar with, as each entails distinct risks and injury patterns (see table 1).

- Bouldering is climbing short routes on boulders or walls without ropes, using crash pads for fall protection.

- Top rope climbing is common in indoor facilities and involves a harness that connects the athlete to the top of the wall with a rope.

- Lead climbing involves the climber placing a rope that they are carrying into pre-existing protection points on the wall as they climb higher.

- Trad (traditional) climbing, primarily done outdoors, is where athletes place their own safety devices into natural rock faces and clip a rope to them.

Table 1: Differences between climbing modalities

| Type | Rope | Protection | Fall Risk | Primary Skill |

| Bouldering | No | Crash pads | High due to lack of safety equipment, but falls are on crash pads | Power and technique |

| Top Rope | Yes | Pre-set anchor | Very low | Endurance and movement |

| Lead | Yes | Pre-placed bolts | Moderate | Clipping and movement |

| Trad | Yes | Placed-gear | Higher | Gear placement and route finding |

Injury Incidence

Bouldering athletes have 1.47 injuries per 1000 hours of climbing, compared with top-rope climbers, who have 0.29 injuries per 1000 sport hours(2). Furthermore, bouldering injuries are more common, likely due to shorter routes that require more intense athletic movements that can stress joints and connective tissues. Indoor climbing gyms commonly offer bouldering as a lower barrier to entry activity. In contrast, top-rope climbing often requires a safety course to demonstrate competence with safety equipment, given its potential for more severe injuries. This policy leads many entry-level climbers to bouldering alone, which can increase injury rates.

Another theory researchers propose to explain why advanced bouldering athletes have higher injury rates is that bouldering-specific shoes often have a more aggressive toe curvature, which can alter the vectors of force during falls onto the ground, resulting in unnatural landing positions(3).

Upper-extremity injuries are the most common among climbers. While proper climbing technique requires nearly equal use of the lower and upper extremities, climbers often place excessive stress on the upper extremities, particularly the fingers, elbows, and shoulders.

“There appears to be clear sex-based differences in injury patterns...”

Injury Patterns

Finger injuries

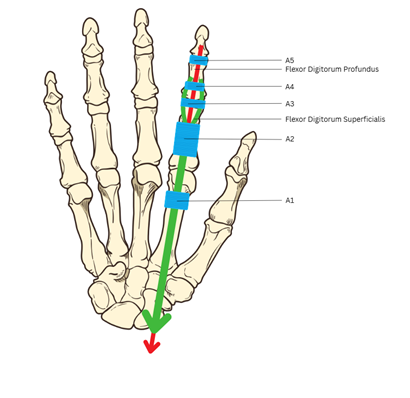

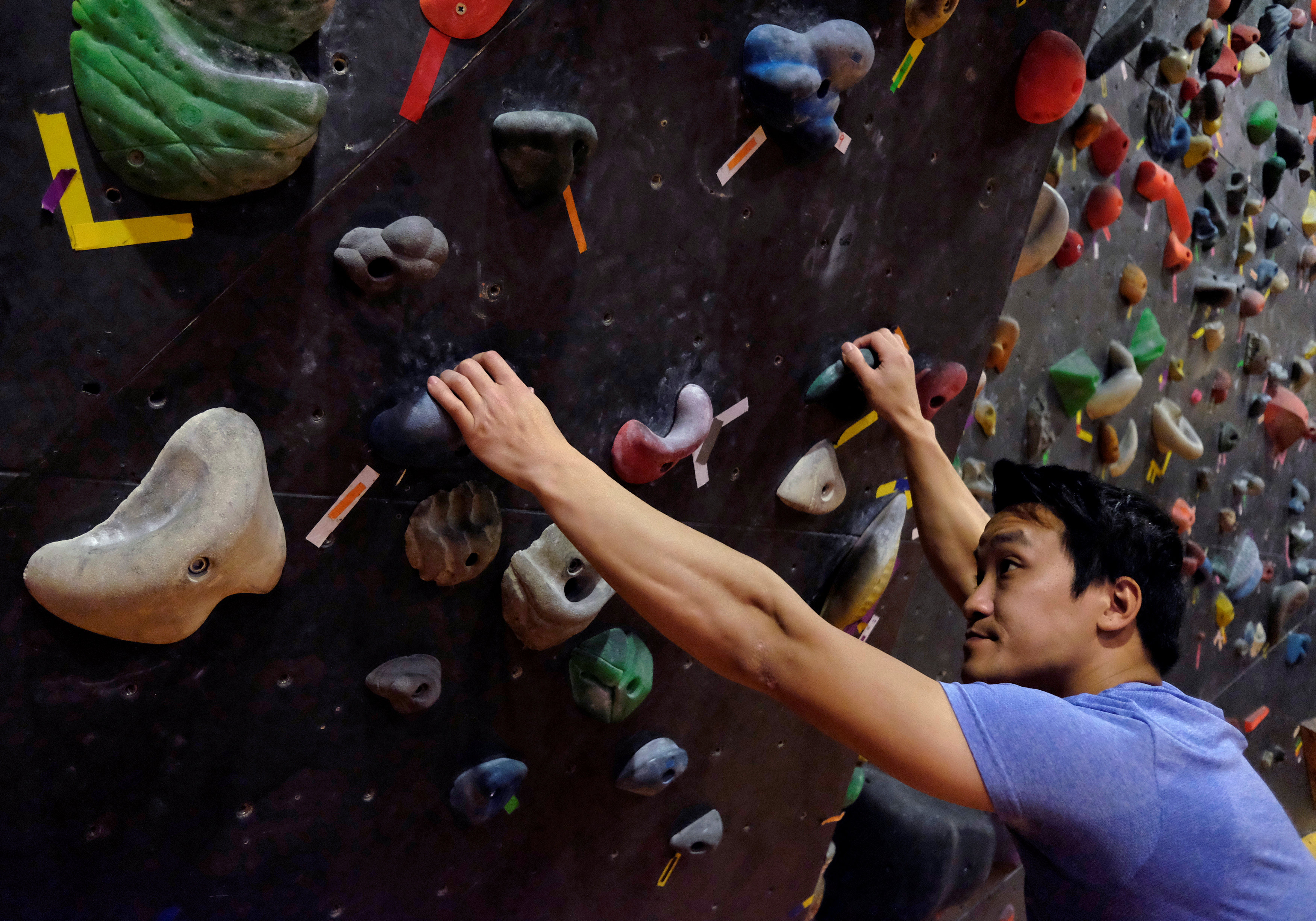

One of the most common injuries in climbing, and colloquially known as "climbers’ finger," is the flexor pulley injury(4). The flexor tendons of the upper extremity digits run across the palmar surface of the hand with transversely orientated fibrous tissue sheaths or pulleys running over them (see figure 1). Climbers place the tendons and overlying ligaments under stress with eccentric loading of the digits during flexion. This mechanism of injury occurs in all climbing disciplines while holding onto "crimps," small outcroppings of rock that are only large enough to hold with the fingers (see figure 2). These outcroppings can extend just millimeters from the wall, requiring climbers to rely on their most distal muscles to support their weight.

While there are five annular pulleys in each digit except the thumb (which has two), the second and the fourth are the most common sites of injury (see figure 1). In a flexor pulley injury, "bowstringing" can occur, in which the affected digit cannot flex to its full range of motion and is associated with local edema and pain. Clinicians grade them on a scale of one to four.

- Grade one: Presents with local tenderness and pain with flexion.

- Grade two: Partial rupture of A2 or A3, or a complete rupture at A4, and involves local pain at the pulley in question, while also having pain with extension of the digit.

- Grade three: A complete rupture of the pulley at A2 or A3, often accompanied by local tenderness, a crack or popping noise, edema, and pain with both flexion and extension.

- Grade four: Multiple ruptures are present or a single rupture with concurrent lumbrical muscular trauma(5).

Clinicians may request hand or finger radiographs to rule out fractures. However, standard radiographs have poor sensitivity and specificity for pulley injuries. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging have similar sensitivities for detecting complete ruptures of the pulley system. Still, clinicians often prefer ultrasound as it is cost-effective, accessible, and can provide dynamic views of the injury. They manage grade one and two injuries conservatively with initial immobilization and early functional therapy, but complete ruptures of A2 or A3 usually require surgical repair(4).

Elbow injuries

The most common elbow injury among climbers is medial epicondylitis. When climbers grab a handhold with their fingers, they strain the flexor muscles of the forearm and wrist. This classic climbing position also involves pronating the hands to reach away from the body (see figure 2). The flexor carpi ulnaris, flexor carpi radialis, and pronator teres share a common tendon insertion on the medial epicondyle. When these muscles are repeatedly strained, the tendon insertion can suffer microscopic tears, releasing inflammatory factors and cytokines(6).

Management is primarily conservative, focusing on rehabilitation and activity modification. When conservative treatment fails, there is growing evidence supporting the use of platelet-rich plasma injection to promote healing in the affected area. Percutaneous tenotomy or surgical debridement of the affected tissue are more invasive options available if symptoms persist(7).

Shoulder injuries

Injuries to the Superior Labrum from Anterior to Posterior (SLAP) tear account for up to 33% of shoulder injuries in climbers(8). Repetitive overhead movements can put a strain on the long head of the biceps tendon anchor attached to the supraglenoid tubercle. The typical mechanism of injury in a climbing setting is a forceful pull on the arm, such as when a climber tries to hold on tightly to a rock face(9). This action is common in bouldering, where climbing routes put climbers in situations that require them to hang on to an overhanging crag. Symptoms include positional pain, often with lifting objects, weakness, and a locking or popping sensation(9). Magnetic resonance imaging is the gold-standard diagnostic tool.

Initial treatment of a SLAP tear includes physiotherapy and analgesic use, with 78% of athletes able to return to climbing after completing a rehabilitation protocol(10). In the remaining quarter of cases, arthroscopic surgery is indicated, with some injuries being amenable to repair of the labrum with suture. In contrast, other injuries require release of the biceps tendon to alleviate the contralateral pulling force on the labrum(9).

Lower-limb injuries

Lower extremity injuries are the most common emergency department presentation in climbing athletes and are mostly limited to trauma-related ankle and knee injuries from falling(8). Injuries include fractures, sprains, and dislocations, and can vary in severity based on the mechanism of the event. The International Alpine Trauma Registry reports that the average height of falls at emergency facilities presenting with sport climbing accidents was 31.4 ± 56 m(11). One-third of the falls reported in the registry occurred among climbers wearing harnesses(11). A five-year sample of United States emergency departments found that one in ten rock-climbing traumas warranted hospital admission for inpatient care or surgery, and less than 1% of all climbing-related presentations resulted in death(12).

“Upper-extremity injuries are the most common among climbers.”

Gender differences

There appears to be clear sex-based differences in injury patterns between male and female climbers. Male climbers tend to report more upper-limb injuries, particularly to the fingers and elbows, while shoulder injuries are common in both sexes. This pattern likely reflects the high grip and pulling demands placed on the upper body during climbing. Female climbers, on the other hand, report relatively higher lower extremity injuries. The factors for this are unknown(3).

Climbing is inherently risky, but proper training, equipment, and caution can help prevent injury among elite and recreational athletes. There is a lack of sports-specific research on rock and wall climbing injuries, leaving clinicians to extrapolate data from other sports. However, as the sport becomes increasingly popular, they will see more of these injuries. There is a gap between the evidence and clinical practice that needs to be filled.

References

- Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2020;10(2):201-210.

- Sports (Basel). 2024;12(2):61. Published 2024 Feb 19.

- BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018;4(1):e000406.

- Wilderness Environ Med. 2003;14(2):94-100.

- J Hand Microsurg. 2022;15(4):247-252.

- Clin J Sport Med. 1996;6(3):196-203.

- Am J Sports Med. 2023;51(9):2506-2515.

- Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2016;45(3):205-214.

- World J Orthop. 2015;6(9):660-671.

- J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022 Jun;31(6):1323-1333.

- Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;17(1):203.

- Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(3):195-200.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.