You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Managing Pace Bowler Workloads

When talking about load management in cricket, most clinicians and practitioners would likely refer to the management of pace bowlers. Although players in all positions get injured, the incidence, severity, and time loss of injuries to pace bowlers exceeds that of batters, spin bowlers, and wicketkeepers. Ross Herridge explores the management of

load in pace bowlers

Cricket - South Africa’s Wiaan Mulder plays a shot off the bowling of Australia’s Mitchell Starc and gets caught by Marnus Labuschagne. Action Images via Reuters/Andrew Boyers

Previously, it has been mistaken that cricket is a sport with low rates of injury, although more contemporary research highlights that this is incorrect, with injury rates being higher in the longer format of the game(1). Although cricket is a skill-dominant sport, it requires a high level of physical fitness to withstand the demands of a match that can last up to five days. For example, team performance can influence the length of the match; some matches can last two days, whilst others can last five days, depending on how well the team bats and bowls, unlike other field sports with more predictable loads, such as soccer.

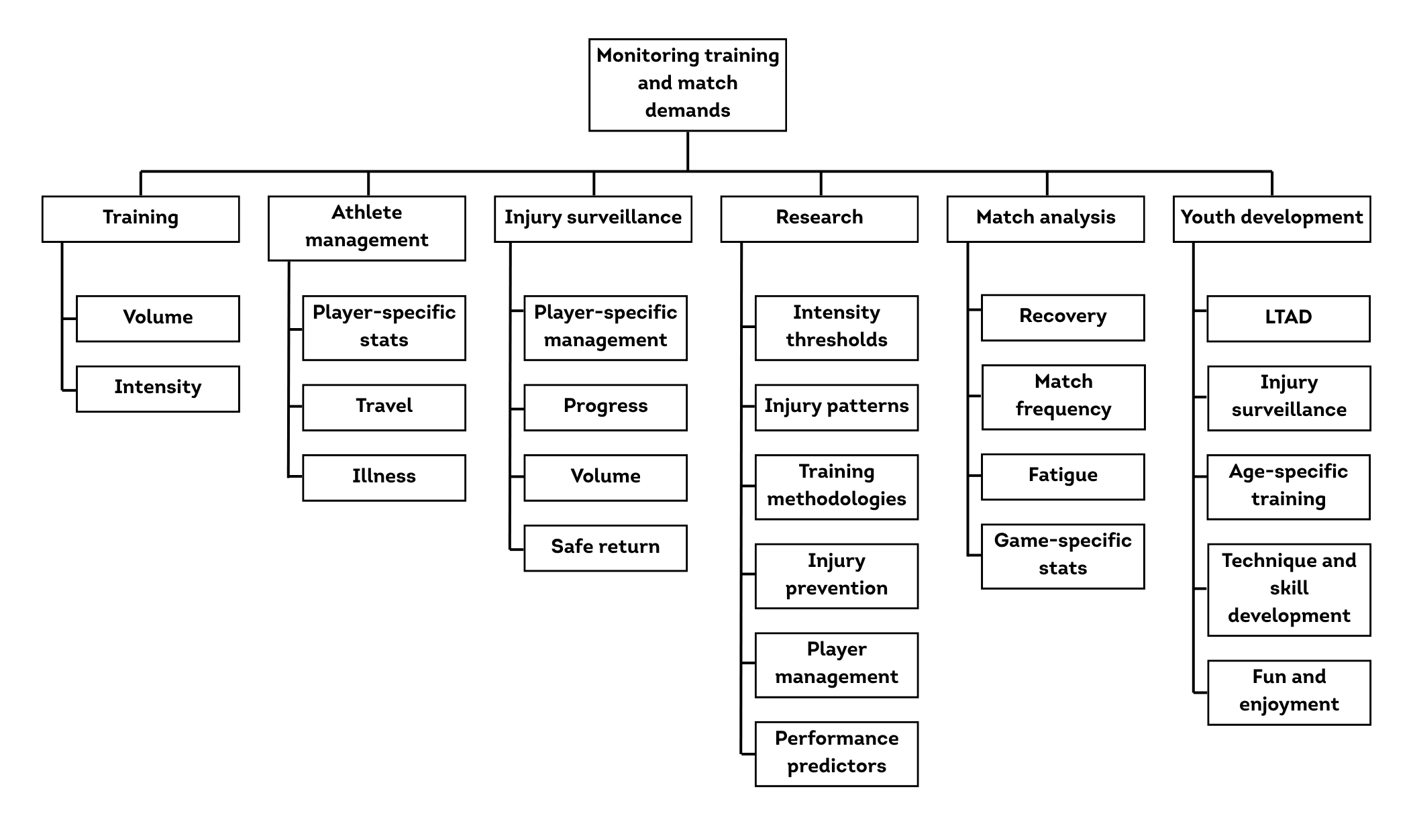

The playing schedule is gruelling: at the elite level in the modern era, players may be involved in various competitions across 12 months a year, from summer to summer across the cricket-playing continents. Whilst batters and wicketkeepers can rely more on their skill to succeed, with lower levels of fitness, pace bowlers are required to perform at a high level, which is a taxing physical challenge (see figure 1).

“…pace bowlers are required to perform at a high level, which is a taxing physical challenge.”

Action Images via Reuters/Andrew Boyers

How Much is too Much?

Monitoring of training load for pace bowlers can be done in many ways using traditional measures of volume, intensity, and density. The most talked about injuries for a pace bowler are lumbar stress fractures due to their time loss, the length and complexity of rehab, and subsequent recurrence rates.

The aim is always to increase an individual’s tolerance by gradually building up training volumes in a deliberate fashion. However, the associated risks include joint, muscle, and tendon injuries that create speed humps along the way. Monitoring individual tissue responses to load is too difficult to capture, so clinicians monitor total system load in terms of pace bowler balls bowled. They capture and collect the volume and intensity of balls bowled during matches and training, as well as weekly and seasonal (yearly) balls. With the premise that athletes tolerate familiar loads and unfamiliar loads are a risk factor for injury, clinicians use progressive overload to avoid injuries associated with ‘spikes’ in both training and match loads.

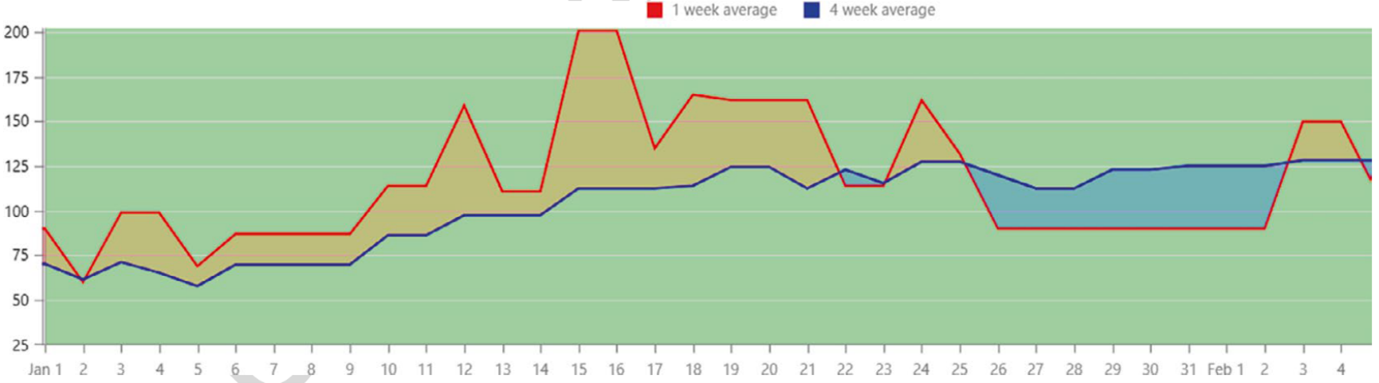

Monitoring an individual player’s training load in cricket is complex; it requires tracking multiple training sessions across different game formats, with varying volumes and intensities (see figure 2). This is intertwined with short and long-haul travel in challenging climates, which adds a layer of complexity for preparation and recovery.

“The game itself has unique challenges for load management…”

Tailoring a program that factors in these variables, as well as recovery modalities for an individual, isn’t straightforward and requires an agile approach in a dynamic cricket landscape(2). For players who now play for multiple teams around the world in franchise cricket alongside international and domestic cricket, optimal load management and planning are increasingly challenging. This outlay goes beyond load management for preparation; coaches and those involved in talent identification can use these systems and processes to nurture and develop younger pace bowlers from junior to elite level. Once they identify young, talented, fast bowlers, they can use the developed processes to ensure players are bowling the optimal amount for their physical maturity and playing level.

Aiming to sequentially build up a bowler’s ability to handle the loads placed on them year on year is the art form required to reduce injury risk. However, this is difficult and involves many variables. Clinicians use the same systems during injury rehabilitation and can return players to a level required to perform, based on what they have been able to withstand previously(3,4).

An example ACWR loading graph for a pace bowler. Where the acute week load is the red line and the chronic (four-week) workload is the blue line. The Y-axis scale is a typical ‘balls bowled per week’ load for a pace bowler in cricket.

The Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio

As in other sports, practitioners use the acute:chronic workload ratio (ACWR) to manage pace bowling load, using balls bowled as the metric. The ratio compares the current (acute) weekly bowling load with the previous four-week (usually chronic) bowling load. They use it across a range of baseline timeframes, including four-, six-, eight-, or 10-week timeframes, and they can collect the reference-week data over three, five, or seven days, although these timeframes yield similar results(5).

The ideal ratio is 1.0 (this week’s number of balls bowled is the same as the average number bowled in the previous four weeks). However, clinicians consider a range of 0.7-1.5 to be low risk for injury. Whereas they consider workload spikes of greater than 1.5 to elevate injury risk(6-8). The nature of cricket, as a high-volume, low-intensity sport, means that practitioners often have to manage peaks and troughs in training and match load. The art in doing so is by flattening out these spikes by increasing the bowler’s ability to handle higher bowling loads. This process takes time — over several years — and that’s why it is critical to monitor bowler workloads from a young age throughout their bowling lifecycle.

Using the Goldilocks theory for workload, not too little, not too much, just right – for that individual.

Seam vs Spin?

The makeup of a bowling lineup can vary depending on the country where the sport is played. In countries like Australia, England, and South Africa, where there is live grass on the pitch, it offers pace, bounce, and lateral seam movement. In these conditions, there is usually a bias towards pace bowlers and pace bowling all-rounders versus spin bowling options. In the sub-continent countries such as India and Sri Lanka, where the pitches are dry and have little/no live grass, there is a dominance of overs bowled by spin bowlers. It’s not uncommon for a team to only carry one to three pace bowling options and more spin bowling options (see figure 4).

Due to factors such as the climate, pitches in these countries are drier, have less bounce and lateral seam movement, and lose considerable pace off the wicket when bowled by a pace bowler. Tactically, teams will set up to suit these conditions, which means the workload on pace bowlers drops considerably. These factors impact the importance of workload management for pace bowlers. Their bowling loads are considerably higher in these conditions, lending itself to more meticulous workload monitoring in these countries and a reason for the dominance of research on pace bowling load management by practitioners in Australia, England, and South Africa, as well as others.

Action Images via Reuters/Andrew Boyers

Practical Implications

The most common units of workload monitoring include distance(s) covered in speed zones, session rate of perceived exertion (RPE, AU), and the number of balls bowled. Practitioners use all these metrics in the acute:chronic workload ratio to progressively overload a player to build tolerance to load. They also capture high-speed running exposures, similar to bowling workload, allowing them to measure loads so players aren’t doing too little or too much high-intensity running, a risk factor for injury(6).

Counting balls bowled seems like a simple task, and practitioners can use self-reported loads at a basic level, and which is still practiced in elite cricket programs. The issue with self-reported load is the potential for false data due to miscounting or errors in data input. Because of this, elite programs are now utilizing wearable technology in training and matches. For example, GPS units capture data to measure running and bowling loads. With these technologies, practitioners can capture bowling intensity, a key variable that influences preparation and injury, and provide deeper content on just balls bowled(9).

There are two major concerns when inferring readiness from bowling loads.

- The accuracy of the bowling loads being reported,

- The assumption that all balls are of equal loading. However, in practice, this is not the case.

Determining bowling intensity provides context for bowling deliveries, and practitioners need it to refine load

monitoring further. Bowling velocity is an option to determine bowling intensity. However, there are some downfalls to using bowling velocity for intensity:

- It is resource-heavy with no easy way to automate data collection in training settings.

- Changing tactical approaches in cricket, particularly in the short formats of the game, athletes may wrongly describe slower balls as low intensity.

- It assumes that all fast bowlers are capable of bowling with maximum velocity at any time. If a bowler can’t reach their maximum velocity due to performance or fatigue, relative intensity could still be high. Therefore, bowling velocity may be a measure of fast bowling performance, rather than intensity.

Elite cricket programs can further refine their intensity measures as they can use GPS technology to detect bowling moments and refine the intensity measures from the gyroscopes and accelerometers(10). Practically, this enables support staff and coaches to more accurately prescribe and monitor fast bowlers in preparation for

competition and return to play settings.

"The art of workload management is dealing with the peaks and troughs of match bowling, the game demands."

Conclusion

The landscape for cricket is becoming more complex; the cricket schedule is growing rapidly with the rise of franchise leagues, and monitoring player workload is harder than ever. The complexity of monitoring not only bowling workload but also factors surrounding the game, such as travel, format changes, and the heat/humidity in which the game is played, can influence the perceived exertion of a pace bowler’s output. The game itself has unique challenges for load management because the game doesn’t have a fixed length of time; from match to match, a bowler may be exposed to vastly different match demands, which influences player preparation. On top of this, not all deliveries are created equal. When a bowler can bowl 240 balls in a test match, the perceived effort from ball one through to the last ball of the match will be wildly different. More contemporary practices have tried to capture this with the use of wearable technologies; this, along with other monitoring modalities, informs practitioner decisions and practices.

References

- Sports Med. 2017;47(3):503–15.

- Indian J Orthop. 2020;54(3):271–4.

- French D, Torres RL. NSCA’s essentials of sport science. Human Kinetics; 2022.

- J Strength Cond Res. 2016;30(12):3464–70.

- Int J Sports Med. 2019;40(9):597–600.

- Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(8):708–12.

- Int J Sports Physiol. Perform. 2017;12(Suppl 2): S2161–s70.

- Sports Med. 2020;50(3):561–80.

- Int J Sports Physiol. Perform. 2015;10(1):71–5.

- Int J Sports Physiol. Perform. 2018;13(2):135–9.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.