You are viewing 1 of your 1 free articles

Prevention of Lumbar Bone Stress Injuries

Lumbar bone stress injuries cause the greatest time loss from playing. Angela Jackson unpacks why clinicians must remain vigilant when working with cricketers with lower back pain and then provides clinical guidelines for managing athletes at risk.

Youth One Day Match - England Under-19’s v India Under-19’s - India’s Vaibhav Suryavanshi in action Action Images via Reuters/Matthew Childs

Cricket participation continues to increase globally, and there are now many more diverse population groups playing the game. Lumbar bone stress injuries (LBSI) cause the greatest time loss from playing, requiring six to nine months of rehabilitation before athletes can safely return to play. Coaches, parents, and players are often unaware of the signs and symptoms of LBSI. Therefore, they often miss these early stages of the condition, which increases the severity of the injury and the potential for non-union. The cricket community needs a large-scale, global exercise-based injury prevention program (IPP) that also includes an education program for coaches, parents, and players addressing known risk factors for injury and how individuals can increase their capacity to mitigate the risks of injury.

Prevention

Cricket has become more demanding physically, with athletes playing multiple formats across the year at the elite level. The injury that creates the highest injury burden in cricket is LBSI, especially in adolescents, 18–23-year-old fast bowlers, spin bowlers, and those who participate in other extension-related sports(1).

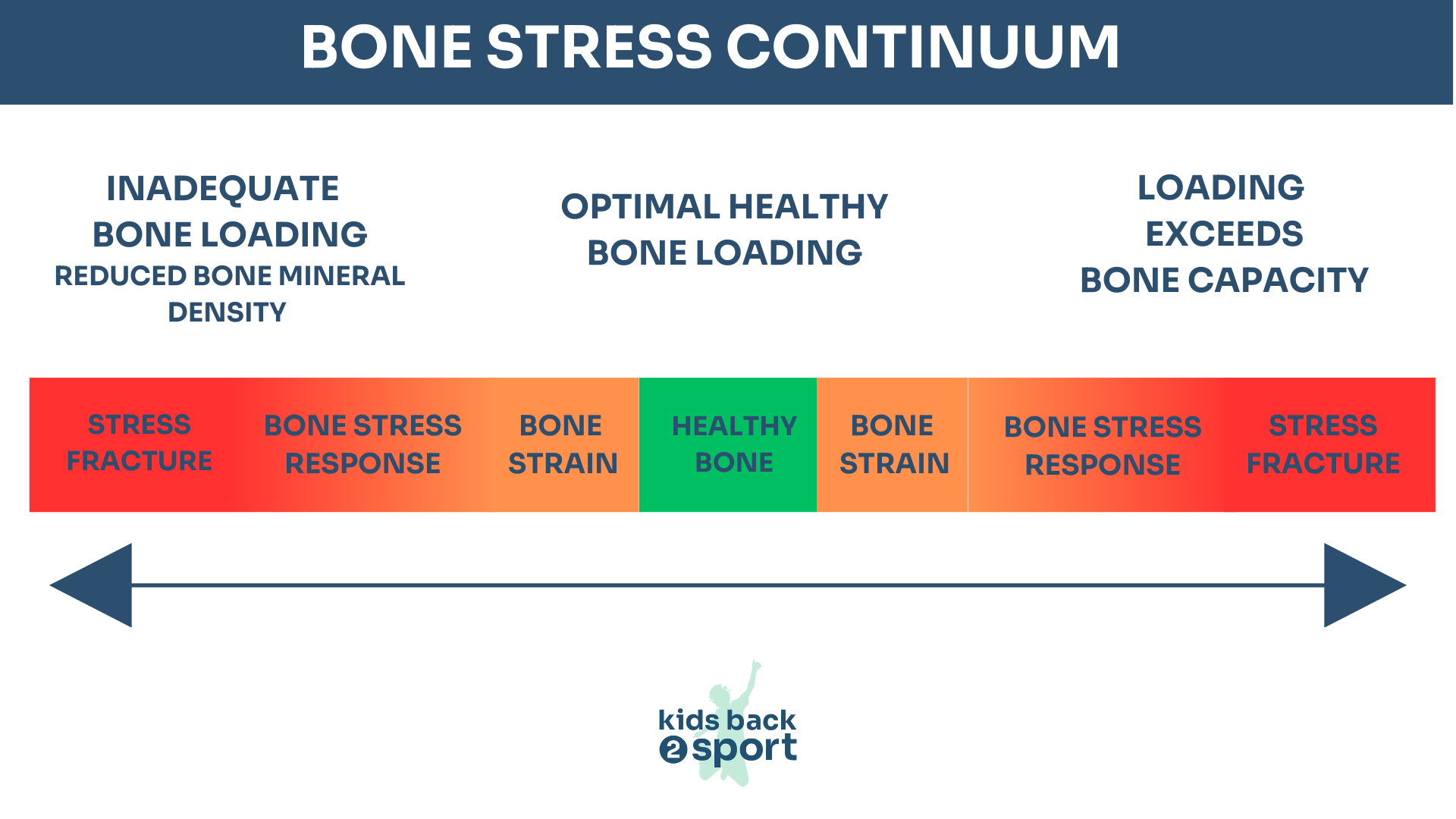

Lumbar bone stress injuries most commonly occur in L4 and L5 on the contralateral side to the dominant bowling arm(2). They can occur at other levels of the lumbar spine and may occur bilaterally, with a greater risk of progression to spondylolisthesis. The lumbar vertebrae do not fully mature and ossify, or acquire peak bone mineral density (BMD), until around 23 years of age in males and, on average, two years earlier in females(3). The fast-bowling action produces high levels of repetitive forces through the immature posterior vertebral arch. In some instances, these forces exceed the bone’s capacity, resulting in an LBSI. They occur along a spectrum from a bone stress response to a stress fracture (see figure 1) using a numerical classification from grade one to four, with higher grade injuries having less healing potential, so early removal from play and diagnosis is essential to maximise opportunity for healing. This window to limit activity and slow down the progression of the injury is often missed due to a lack of awareness of the condition amongst stakeholders.

“…a global shift in injury prevention across cricketing nations…”

Risk Reduction

Reducing the risk of LBSI is crucial due to the potential for prolonged time loss from the game. Recovery to full sport participation requires intensive rehabilitation of between six and nine months, which may result in players dropping out of the sport. Cricketing organizations have implemented strategies to reduce the risk of LBSI, but to date, there have been few successful interventions outside of the elite setting.

Injury prediction is complex, and there are multiple conflicts in the literature regarding risk factors for developing a LBSI, ranging from technical, biomechanical, and musculoskeletal factors, and spikes in bowling load beyond the athlete’s capacity(4,5). However, what constitutes a risk factor for one person may not affect another, and an individual’s capacity to tolerate load fluctuates in response to altered sleep patterns, energy availability, stress, and growth spurts.

Injury Prevention Programs

A higher degree of hip flexion in back foot contact in young fast bowlers correlates with a greater risk of LBSI(6). Inadequate single-leg strength and trunk stability may contribute to these associations, but there is no existing cricket-specific neuromuscular IPP(7). Practitioners have successfully implemented programs such as FIFA 11+ in soccer, with a meaningful reduction in injuries(8). For any injury prevention program to be effective, athletes must do it consistently. This means that it must be cost-effective, require minimal equipment, be time sensitive, and be easy to implement without the presence of highly qualified coaches.

New Zealand Cricket Youth Pace Bowling Guideline(11)

- F – Frequency – Number of bowling sessions in a week.

- I – Intensity – How hard a player works in those sessions.

- R – Rest – How much should the player rest to recover well.

- S – Surface – Awareness of the differences between indoor and outdoor surfaces.

- T – Type of Training – Skill development, technical, tactical, competitive.

Musculoskeletal Screening

Researchers and coaches have advocated for multiple technical approaches to facilitate greater bowling pace and mitigate the risk of injuries. However, these often fail to account for individual biomechanical differences, which may increase the risk. In the elite setting, clinicians use musculoskeletal screening to identify individual risk factors and use the results to guide the suitability of specific approaches. However, a lack of resources would limit the viability of this approach in community settings.

Imaging to Increase Early Identification

The gold standard for diagnosing an LBSI is MRI, and it may be a useful early-detection method for identifying athletes who may be at greater risk of developing a more significant injury(9). However, there is a conflict in the literature regarding the reliability of the results across different population groups. Furthermore, MRIs are expensive, and accessibility to scanners is limited outside of elite settings.

Is Bowling Too Much the Problem

Clinicians have traditionally associated LBSIs with high bowling loads where players simply did too much, too soon. Cricket governing bodies implemented junior fast bowling directives, capping daily bowling volume according to age, to combat this risk. However, to build up lumbar BMD, it takes years of repetitive bowling to generate adaptations adequate to withstand the demands of the adult game. Athletes largely accrue BMD during adolescence, and limiting juniors from bowling may hinder protective adaptations from developing. In addition, many fast-bowling directives fail to consider the large differences in maturation between children of the same age or consider how not all balls are equal when quantified in terms of intensity. Children eager to impress often bowl at maximum effort on every delivery in both training and match environments, which may place an adolescent athlete at a greater risk of injury(10). To address this, New Zealand Cricket advocates a F.I.R.S.T. approach in their Youth Pace Bowling Guidelines, which account for not only the volume but also the intensity of each bowling session(11).

A spike in load following a period of relative inactivity can increase the risk of injury, such as after an injury or the start of a new season. Governing bodies encourage a gradual build-up in bowling load in preseason to build load tolerance, and some advocate a low load bowling week mid-season(12). Despite these guidelines, many young players eager to play fail to adhere to them, and coaches struggle to track and monitor loads across all the different settings and sports in which junior players participate.

“…what constitutes a risk factor for one person may not affect another…”

Individual Variability

Load alone does not explain why some athletes sustain bone stress injuries and yet others exposed to similar loads remain injury-free. When players are tired, stressed, experiencing a growth spurt, or failing to fuel adequately, there may be a decrease in their capacity to tolerate load.

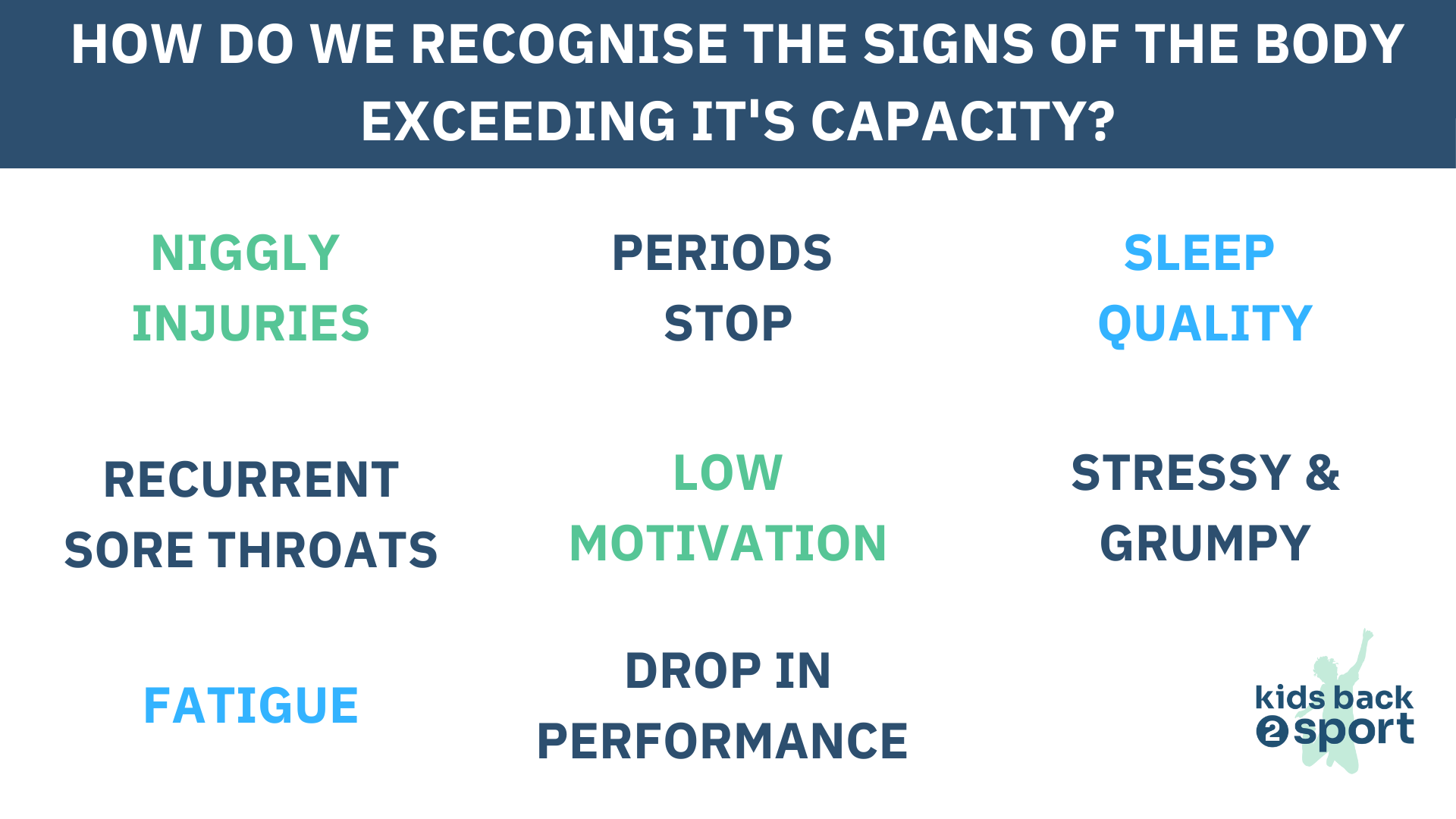

Athletes need to maintain a positive energy balance where energy intake exceeds energy expenditure. Low energy availability (LEA) can trigger a downregulation of non-essential hormonal processes, affecting multiple bodily systems, including bone synthesis, and heightens susceptibility to LBSI(13). A lack of awareness about the energy requirements of youth athletes increases the likelihood that they will fail to reach their full potential. Clinicians must focus on education regarding the signs and symptoms that indicate when an athlete is exceeding their current capacity (see figure 2).

Careful monitoring of wellness and performance is pivotal to successful athlete management. Before training, parents and coaches can use simple wellness questionnaires to assess the athlete’s readiness to train and determine how well they are coping with the current load (see table 1).

Regular use of this concept, likening their energy to the battery in their mobile phone, can help players listen to their body and moderate training accordingly (see figure 3).

- Go hard: If players are tolerating the loads applied without injury or illness, there is no reason to limit their development, provided the increase in load is gradual and planned.

- Go easy: On days when they have moderate energy levels, they could focus on technical or tactical skills and avoid high-intensity drills.

- Go home: On days when the player reports higher levels of soreness, tiredness, or stress, clinicians and coaches should encourage them to miss a training session – better a session missed than a season.

Education of Players and Stakeholders

Simply being stronger is not enough to reduce the risk of injury. Many of the known risk factors could be mitigated if players and coaches are more aware of approaches load according to how well it is being tolerated. To address this need in cricket, the author has created a program called Ready 4 Cricket, combining both strength and education programs. This needs to be validated, and a top-down approach is needed to support coach education. The key factors include:

- The importance of a graduated loading program,

- Planning for adaptation days and diarizing a low-load week every four to five weeks,

- Maturation appropriate warm-up, and IPPs,

- The importance of tracking growth to identify those athletes whose growth spurt is occurring fast or exceeds 7cm per year,

- Assessing maturation to identify late developers to ensure they are not exposed to inappropriate loads for their skeletal maturity,

- Actions required when a player develops low back pain,

- The need for positive energy balance to meet the demands of wellness and sport,

- The signs when energy needs are not being met or capacity exceeded to maintain wellness and bone health,

- How to boost an athlete’s capacity to tolerate more.

Table 1: Simplified wellness score using a 1-5 scale, where 5 indicates readiness to train and 1 indicates a need for greater recovery

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|

Soreness |

|||||

| Fatigue | |||||

| Stress |

Future Considerations

The long-term implications of sustaining a LBSI that fails to heal are not clear. However, anecdotally, managing not to sustain this injury in the early career of a professional fast bowler leads to longer-term test careers than those who do not(15). The higher the grade of injury, the less optimal are the chances for bony healing and the greater risk of injury progression. To successfully reduce the high incidence of these injuries in junior players, a substantial investment is needed to develop effective education for coaches, players, and parents. This approach necessitates a global shift in injury prevention across cricketing nations, but it is essential to truly impact the incidence of LBSIs.

References

- BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, May 1;5(1):e000529.

- Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2021 Mar 1;53(3):581-589.

- Bone. 2020 Feb 1;131:115163.

- Br J Sports Med, pp. 50:1309–14.

- BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation volume 15, Article number: 114 (2023).

- J Sci Med Sport. 2016 Feb;19(2):117-22.

- Physical Characteristics Associated With Lumbar Bone Stress Injury Related Technique In Male Fast Bowlers. 2024. ISBS Proceedings Archive. P. 42(1):1030.

- Sports Med. 2016 Feb;46(2):205-17.

- Bri J of Sports Med, pp. Oct 1;53(19):1236-9.

- J Sports Sci. 2022 Jun;40(12):1336-1342.

- Cricket, New Zealand. Youth Pace Bowling Recommendations. New Zealand Cricket.

- Cricket, England. Recreational Fast Bowling Guidance. England and Wales Cricket Board.

- Sports Med. 2022 Jun;52(6):1223-1234.

- Jackson, Angela. Kids Back 2 Sport. www.kidsback2sport.com.

- S Afr J Sports Med. 2023 Jun 5;35(1):v35i1a15172.

Newsletter Sign Up

Subscriber Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Newsletter Sign Up

Coaches Testimonials

Dr. Alexandra Fandetti-Robin, Back & Body Chiropractic

Elspeth Cowell MSCh DpodM SRCh HCPC reg

William Hunter, Nuffield Health

Be at the leading edge of sports injury management

Our international team of qualified experts (see above) spend hours poring over scores of technical journals and medical papers that even the most interested professionals don't have time to read.

For 17 years, we've helped hard-working physiotherapists and sports professionals like you, overwhelmed by the vast amount of new research, bring science to their treatment. Sports Injury Bulletin is the ideal resource for practitioners too busy to cull through all the monthly journals to find meaningful and applicable studies.

*includes 3 coaching manuals

Get Inspired

All the latest techniques and approaches

Sports Injury Bulletin brings together a worldwide panel of experts – including physiotherapists, doctors, researchers and sports scientists. Together we deliver everything you need to help your clients avoid – or recover as quickly as possible from – injuries.

We strip away the scientific jargon and deliver you easy-to-follow training exercises, nutrition tips, psychological strategies and recovery programmes and exercises in plain English.